By Ghosts, For Ghosts: Pandemic-Era Virtual Horror Theater

In this show, I play a ghost. My name is Glitch, but to everyone in-world (a haunted summer camp), I am a question mark. I have no face and no name. I drift through walls. In one room, there is only one person. I watch their face for a long time while they try to communicate with me through Zoom chat, Zoom being where we are.

“Who are you?” they write.

“What do you need?” “Are you a ghost?”

I find myself fixed on their face. It’s 2020, a year in which I co-wrote and produced a queer apocalyptic cabaret that will never be funny again because of the actual apocalypse. It’s Pride Weekend, when I would normally be touching so many strangers, dancing body to body, maybe kissing some, but this is what I have, the closest I’ve been to a stranger in months. I am Not Here. They can’t see me. I can’t touch them. I am a ghost. I want to cry, but this is their show after all.

“Boo!!” I type. I disappear into the next Zoom breakout room. Often, I don’t chat. I listen to people talk. One time, an audience member says to her partner, “Look! Ghost!” Before the partner can see me, I’m gone, laughing. Ghosts have to leave a measure of doubt. Audience members who have seen me blame Glitch the Ghost for all kinds of things – wifi trouble, actors freezing, break-out room mishaps. If something goes wrong during the show, they smile. I experience what it is to be a ghost: no one can hear me or feel me unless I make a ruckus or unless they’re listening. My presence is smaller, but in their perception, I can be in many places at once.

Immersive horror theater has huge potential in a global pandemic that requires us to be physically separate while at the same time giving us more and more tools for connection. I want to highlight some theater companies that are doing this work, which is simultaneously ancient and barely embryonic, and imagine it as a practice run for storytelling in What Comes Next: climate apocalypse, zombie apocalypse, our increasing consensual digitization. I want to consider immersive virtual horror theater in the tradition of what horror does best: as utopic, slicing a perfect piece of the Worst as a way to glimpse its opposite; as trauma therapy for all those of us who live in a horrifying world; and/or as genre, and therefore as Carmen Maria Machado wrote, quoting Kelly Link, “promising pleasure.” I want to do all that, while imagining a short play, this one, in which I am a ghost, and you might be one too. Most of us have been a ghost to someone. We circle around places, like this one, where the ghost light is still on.

But first, definitions and examples. Immersive theater is theater where there is no stage, and the audience is immersed in the world of the show. A classic and early example is Punchdrunk’s reimagining of Macbeth, Sleep No More, in which audience put on a mask and wander for hours in a warehouse block in Chelsea, following actors, exploring the world of the set. When I went, I found myself alone in what looked like an 18th century operating theater. I stretched out on the table and scared myself silly. Immersive theater exists on a spectrum. Breaking the fourth wall, the imaginary wall between actors and audience, or even drawing attention to it, is a form of immersion. The dial is closeness.

On a different axis is interactive theater. Interactive theater is theater that lets you participate in the outcome of the show. The dial is agency. One example was Marie Antoinette, a late 1990s French interactive production depicting her trial, in which the audience was allowed to vote on her fate: execution, exile, or acquittal. When I saw it, the theater company had introduced a double ending because they couldn’t get the audience to not vote for beheading. The guillotine was on the stage. We were in the country that gave us the Grand Guignol. Something old and scary and deep happens when you get a group of people together and play out a sacrifice. When the blade came down, no one breathed.

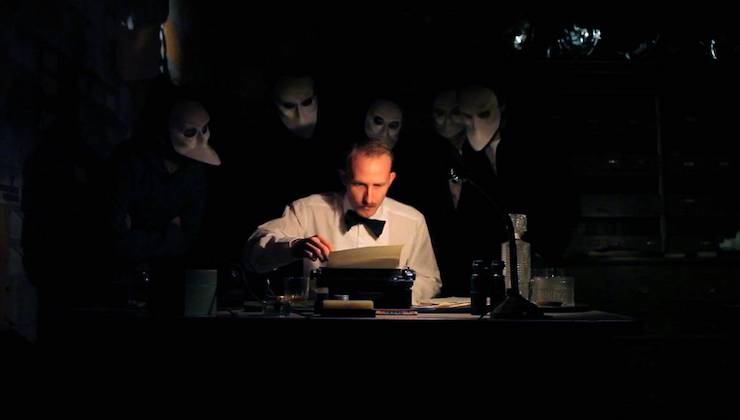

Of course it was only a matter of time before immersive theater found its way to horror. Delusion immerses the audience in a 1970s Hammer horror world. Peaches Christ’s Haunted House at the SF Mint is a classic, and Josh Randall and Kristjan Thor’s 2009 Blackout comes complete with a waiver for psychological torture ranging from strobe lights to people yelling at you to the staging of your own greatest fears. Blackout generated its own documentary, in which audience members describe going in for that treatment repeatedly.

Let’s note, while we’re ghosts, that immersive theater and interactive theater are terms that imply a very Eurocentric understanding of theater’s history, one that begins in Greek Tragedy, continues through a whole lot of sitting in seats, and branches off with companies like Punchdrunk. But participatory performance is as old as theater and doesn’t require a warehouse. (See: Ghosts Scare Indonesians Away from Coronavirus).

And there’s plenty of room for unintentional horror in the immersive experience: you get stuck in the maze, you get pulled up on stage when you don’t want to, the white rabbit yells at you to turn the knob, but nothing happens. Sometimes–often–the audience behaves badly.

But the thing that makes immersive theater magical–the absence of a stage–is also the thing that makes it so perfect for our current moment. When you move traditional theater, including traditional horror theater, online, you often get something between a webinar and a not-so-great movie. When you move immersive or interactive theater online, the world broadens, and the boundaries blur. You are made aware of the flimsiness of this shared reality, and just how quickly you can dive into another one. (What if I were really a ghost? What if I told you not to look behind you right now?)

Consider Candle House Collective’s Claws, in which a young person calls you for advice on how to handle the monster in their closet. It’s immediate. It’s on your phone. You are responsible for what happens next. Or Darkfield Radio’s Double, a show intended to be experienced in your house, with a person you love, and that plays with Capgras Delusion, the conviction that your person has been replaced by an impostor. Or The Visitors, in which you and someone in your home play ghosts, unable to touch.

Prefer something even more immersive? Got a VR headset? Join me at Krampusnacht VR, which promises live actors and probably jump scares. Want something that blurs the lines between what’s real and what’s not real? Virtual Frights by Pseudonym Productions is a show that has “no beginning, and no end.” If you are reading this, the story has begun. How’s that for immersive?

Why would someone want to be part of a horror world? Maybe it’s growing up with horror, or having the sense that we already live in an immersive horror world, especially these days. We want our chance at agency. We want our chance at monstrosity. We are getting good at being ghosts. Maybe we know deep down that we already have the platforms that allow us to collaborate on a shared story, and when we aren’t intentional about it, those stories can get pretty horrible (see also: Facebook). To be part of an immersive horror show is also to realize that the potential for horror (of the delicious sort) is still present even now: an online meeting room in which the audience disappears one by one, a Zoom background that looks like you’re endlessly walking in on yourself at the same meeting, a TikTok that goes viral. A stranger in Gather Town. If we can imagine the horror potential of something, maybe we can also imagine its utopic potential.

Or maybe there is something about live theater that has always been haunted. Theater has ghost lights, exits that aren’t real, a rotating platform designed specifically to show you something horrible. There is a theater in Paris that has been showing the same performance every single night for over 60 years, most of those with the same actors. Eugie Foster’s devastating When It Ends, He Catches Her engages with theater’s eerie nature. It’s a haunted group ritual that allows us to rehearse some basic lessons together: stay together, don’t look behind you, don’t say the name of the Scottish Play. Virtual immersive online theater means we can do it right now.

Let’s welcome this new(ish) genre. We are practicing for a post-ghost world. We are survivors in this horror we helped create, and can help uncreate. It’s no coincidence we’re in this room. We can change the shape of the story together.

To learn more about upcoming immersive horror events, check out Everything Immersive and Haunting.net.

This post was written for Nightfire in partnership with Pseudopod.