Looking Into the Eyes of José Mojica Marins’ Coffin Joe

José Mojica Marins is sort of what Antonio Carlos Jobim is to jazz, but for horror movies. Like Jobim, Marins took inspiration from American artists, but gave his work a Brazilian spin, which in turn inspired a lot of subsequent American followers. He will be forever known as Josefel Zanatas, a.k.a. Zé do Caixão, or as he is called in English, “Coffin Joe,” an undertaker who made house calls, even when his customers weren’t expecting him. Whereas Jobim was widely celebrated abroad and at home, Marins (the son of Spanish immigrants) achieved a degree of notoriety in Brazil, but domestic critical respect largely alluded him during his lifetime, despite achieving a cult following in America for his unique blend of nihilistic philosophy and slasher horror.

Many consider him the inspiration for Freddy Krueger. After all, they both sported rakish hats, had long, lethal talons (in Marins’ case, his trademark fingernails were the real, home-grown deal), and each really loved to talk. They also shared odd career parallels. Coffin Joe introduced the anthology film, The Strange World of Coffin Joe in 1968, twenty years before Freddy’s Nightmares premiered on TV. In later decades, Coffin Joe appeared in-character as a Brazilian television host for several horror movie showcases, perhaps the most notorious being Cine Trash.

Only the Coffin Joe “trilogy” (available as a 3-DVD set from Synapse Films) is considered strictly canonical, but Marins also appeared as himself and his infamous alter-ego in several films of vastly varying quality. In The Bloody Exorcism of Coffin Joe, Marins is terrorized by his fictional creation, conjured in the flesh by an unholy ritual, which again predated the meta-ness of Wes Craven’s New Nightmare by almost twenty years.

Originally, Marins did not expect to play Zé do Caixão himself, but when the original actor he cast dropped out at the last minute, the director stepped in. Coffin Joe’s debut, At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul, is widely recognized as Brazil’s first horror film. Zanatas was a mortician by trade, but he intimidated and humiliated his provincial town through the sheer force of his will. In fact, Coffin Joe is so convinced of his superiority, he is driven to achieve immortality for his bloodline, by having a son with the perfect woman. Unfortunately, his wife is sterile, so he kills her with one of his preferred methods of execution: deadly tarantulas. In Coffin Joe movies, the bugs and snakes were almost always real, as Jon Stewart found out the hard way, when Marins visited his early-1990s talk show.

Inevitably, Coffin Joe decides the fiancée of Antonio, the only man in town who (mistakenly) considers him a friend, would be the perfect mother for his son. In case of awkward timing, he decides to kill the unsuspecting Antonio after their planned visit a Romany fortune-teller. Like Maleva in Universal’s 1940s Wolf-Man movies, the old woman immediately recognizes his evil intentions and warns him fate will thwart his desires, through fatally uncanny means.

Ironically, even though Coffin Joe is a virulent materialist, he is constantly undone by the supernatural (such as curses and ghosts). He also has an almost superhuman constitution, judging from the fact he managed to survive his apparently violent demise at the end of the first film.

It turns out good old Zé was only temporarily blinded by the spirits of his victims. After a little bed rest, he is good as new, so he can continue terrorizing his town in the sequel, This Night I’ll Possess Your Corpse, produced three years later. Coffin Joe soon returns to his old tricks, assembling a group of scandalous, irreligious women, whose Nietzschean mettle he puts to a series of extreme tests. In real life, one of the women was nearly suffocated by Marins’ snakes.

In Possess Your Corpse, we learn Coffin Joe has a soft spot for children, because he considers them unspoiled by corrupt religions and bogus superstitions. Therefore, it uncharacteristically troubles Coffin Joe when he learns one of his latest victims was pregnant, eventually even inducing visions of Hell. The garish color of this lurid sequence stands out in stark contrast to the grungy black-and-white. It is wildly psychedelic, in an unsettling way, very much like the images of damnation in Nobuo Nakagawa’s classic Jigoku (or Hell). Yet, Marins probably realized them at a fraction of the cost, while utilizing nonprofessional actors (who were bizarrely comfortable with the required nudity, given their largely middleclass tradesmen backgrounds).

After over forty years of failed attempts, Marins finally finished his trilogy with the Embodiment of Evil. Again, he manages to retcon away Coffin Joe’s supposed death in the prior film. He also took great satisfaction in undoing the Christian ending mandated by the old military regime. Instead of embracing God with his dying words, Joe pops out of the water again, to kill a few more villagers, before he gets hauled away to serve a long prison sentence. To film the additional flashback footage, Marins hired a dead-ringer lookalike to his old 1960s self, who had posted fan videos on the internet. Honestly, it is eerie how seamlessly Marins blended the new supplemental flashbacks with the black-and-white scenes from the 1967 film.

Frankly, the violence of Embodiment is harsher and more graphic than anything in the previous films in the trilogy. Yet, in much the same way the prior films attacked the hypocritical morality of the military era, Embodiment directly challenges the tactics and alleged civil rights violations committed by Brazil’s regional paramilitary police forces in the favelas (the BOPE in Rio being the most notorious). In many ways, this film could be called “Coffin Joe vs. the Elite Squad.”

Sadly, one of those officers was played by Jece Valadão, an actor known for playing cops in trashy films, who died during the production. As a result, Adriano Stewart was subsequently hired to play his brother, a fellow police officer, replacing Valadão in the scenes Marins had yet to film. It all climaxes in São Paulo’s Playcenter amusement park, where Marins used to host nighttime horror screenings, until it closed.

Playcenter was also home to the Coffin Joe Museum, which to this day has yet to find a new home. Fans will be similarly frustrated if they hope to find a Coffin Joe walking tour of his kills across São Paulo. The small Brazilian press Darkside Books released Andre Barcinski & Ivan Finotti’s Zé do Caixão: a Biografia, but you will not find it in most Brazilian bookstores (however, there is one bookseller in a São Paulo mall Leitura store who will be thrilled if you ask). It is quite an object to hold in your hands, almost like a copy of the Necronomicon.

In truth, if you ask many Brazilians about Coffin Joe, they will look at you like you’re nuts. Unfortunately, Marins’ lean years defined him for many of his fellow countrymen. They know him as the host of Cine Trash, which showed some pretty graphic gore at 2:30 in the afternoon. Even for diehard horror fans, it is kind of shocking how much blood and guts they allowed for their promotional spots.

Sadly, Marins even directed two hardcore porn movies that were notorious for their own Coffin Joe-esque excesses. Even an icon has to pay the bills. Things got so bad at one point, Marins agreed to cut his trademark fingernails on live TV, because he needed the money. Nevertheless, this was the same subversive Coffin Joe, who mounted a gadfly political campaign for a São Paulo state office.

Many of Marins’ pseudo-Joe movies are dismissed as exploitative cash-ins, sometimes with justification. Outside of the trilogy, Marins’ anthology, The Strange World of Coffin Joe is probably the closest to the look and texture of his first two Coffin Joe films. The old man in the opening story, “The Doll Maker,” even resembles the older Marins a bit, but he was played by Jayme Cortez. Anyone who has seen a lot of horror anthologies will wonder why the would-be home invaders never stop to consider how the titular doll maker creates such lifelike eyes, but they don’t—until it’s too late.

Instead, after introducing the film as Coffin Joe, Marins appears in the third story, “Ideology,” portraying the very Zé do Caixão-like Prof. Oãxiac Odéz, who basically does for sex therapy what Coffin Joe did for mortuary science. Odéz has invited his prominent media critic and his wife to his spooky home, to break them down and mold them into his mindless minions. Even though it was just one year after Possess Your Corpse, “Ideology” is dramatically more violent and graphically explicit. By this point, pushing the envelop was an established element of Marins’ brand, which he would stay true to throughout his checkered career.

Whether it is canonical or not, every fan-satisfying Coffin Joe film has to have a scene of Marins’ cold, bloodshot eyes staring at the camera, while he gives a bombastic monologue explaining how people are weak and stupid, concepts like “good” and “evil” are meaningless, and any philosophical system of epistemology is by definition total rubbish. Coffin Joe had a way of giving his audience a stern talking-to, but still getting them to come back for more.

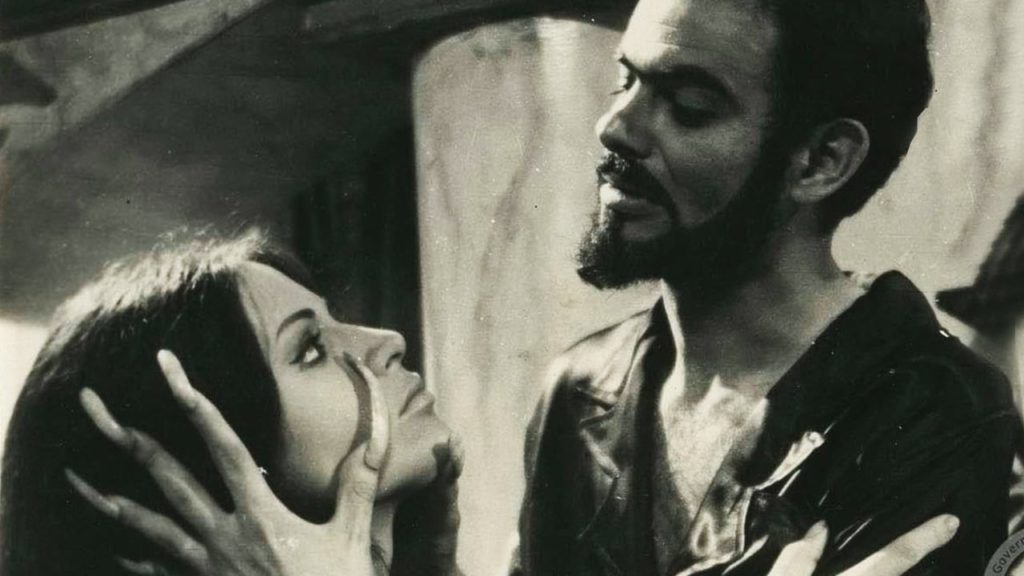

The 1960s Marins was relatively small in stature, but he had an enormous screen presence. There is something very archetypal about Coffin Joe. He is that person whose aggressive personality automatically dominates a room as soon as they enter. That truly comes through in At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul and This Night I’ll Possess Your Corpse, which ought to be considered masterworks of world cinema, above and beyond mere cult favorites. Any horror fan really needs to see those two films (and from there, you’re on your own, based on your preferences for gore).

Marins passed away two years ago, but his Coffin Joe persona remains a true horror icon, who should have equal standing with the likes of Michael Myers and Jason Voorhees, if not greater, due to his Nietzschean superiority. As he often told us, the proof is in the blood—and there was a lot of it.