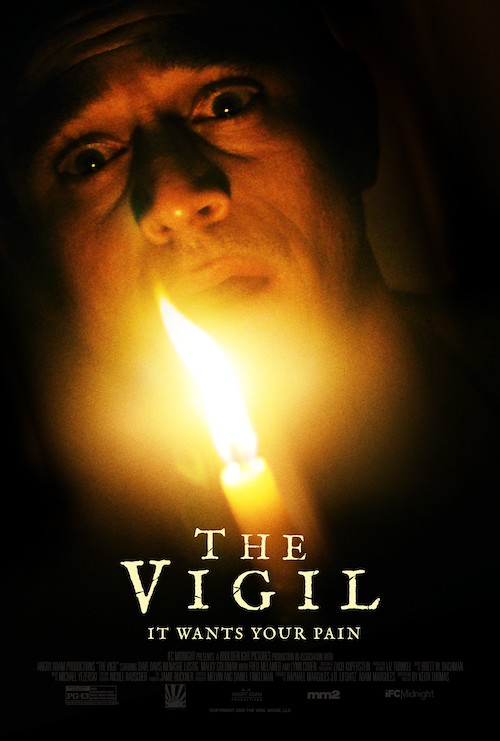

No Good Mitzvah Goes Unpunished in The Vigil

The Vigil is a taut, atmospheric horror story—it clocks in at just an hour and half, tells a perfectly constructed, terrifying story, and while it’s obviously an extremely small, indie production, it (mostly) uses that to its advantage. The entire film unfolds over two apartments and a couple blocks in the Borough Park neighborhood of Brooklyn. Most of the story rests on two traumatized characters, a young man named Yakov Ronen (Dave Davis), and the newly widowed Mrs. Litvak (Lynn Cohen), who are both immediately compelling. And most important, the movie relies on deep shadows and claustrophobic atmosphere to generate horror, and, for the most part, it works. There are also some really fun nods to The Exorcist, Halloween, The Evil Dead, and The Blair Witch Project that play on our expectations and very much place this film in a solid horror lineage.

As I’ve discussed (at length!) over at Tor.com, I love the sub-genre of religious horror. Any time you add an exorcism or a conflicted priest or Viggo Mortenson-as-Satan to your movie, I’m going to love it a little bit more than if there are just, say, zombies or extraterrestrial shapeshifters or Freddie Krueger or whatever. Setting a story in a universe that has ancient, stone-carved rules—some of which apply in our own world—adds a level of tension that you can’t get in a world that has been manufactured for those rules. Like, vampires and werewolves can be killed in certain ways because those weaknesses were built into the lore around them as that lore was created. We enter a vampire story knowing that either the vampire will be killed with a stake through the heart, or that the storyteller will subvert Chekov’s stake. We enter a religious horror knowing that the characters mundane lives are about to get up-ended in a way that might not be fixable.

The problem with religious horror, though, is that generally a person’s first thought is The Exorcist or The Omen or Rosemary’s Baby or Paul Bettany playing a priest. Catholicism has pretty much dominated the market. One of the most exciting aspects of The Vigil is that it gives us a great Jewish horror story.

The Vigil opens with the scariest thing a horror movie can give you: white text slowly fades up on a black screen, explaining the ritual you’re about to see. The Vigil, or Shemira, is a common Jewish practice. In the first few days after death, a person’s soul is vulnerable to attack from demons (and, more prosaically, their body is vulnerable to vermin) so the family sits up with their loved one’s body to protect it–and also to have private time to say goodbye before the funeral. Ideally, it’s a beautiful liminal space for people to grieve. But what happens if a person doesn’t have family to watch over them? That’s when you call in a stand-in Shomer, a person who is hired to sit up with the body until it’s ready for burial. Kind of a quieter version of professional Irish keeners.

This is already a great set-up for horror: the baseline is that a person has to sit quietly in a room with a dead body, waiting for dawn to come. You’re not supposed to have music on, or spend the time texting all of your friends, or distract yourself too much from the reality of what you’re doing. Where The Vigil takes it to another level is in a series of perfect details that gradually turn the Shemira into a terrible trap.

In one of the film’s great strengths, it explains very little after that title card, expecting the audience to keep up the same way a Troubled Catholic Exorcist Movie would. We meet Yakov when he attends a small meeting in an apartment, and only gradually realize that it’s a support group for people who have left the Hasidic community. There’s a range of people at the meeting—one woman who dresses modestly, another in a short-sleeved shirt; a man who wears a full beard and a yarmulke, another who’s clean-shaven and bare-headed. Yakov looks a bit more casual, but his long sideburns are what’s left of the payess he cut off, and he’s still trying to figure out how to use his new phone, since he had very little access to tech in his old life. We also learn that he’s having trouble adjusting to social life (and making rent) outside his community.

When he’s enlisted by his old friend Reb Shulem (Menashe Lustig) to act as Shomer, we know he’s only doing it for the cash, and we feel Yakov’s mounting frustration as Reb Shulem pressures him to come to Temple and return to the fold. So, a hero in a precarious emotional/spiritual position? Check. But wait, there’s more! We slowly learn that Yakov is coping with PTSD, and he’s on a dwindling supply of meds. Finally, as the two men walk to the Litvak’s home, Reb Shulem explains that he needs a Shomer because Mr. Litvak was a recluse, the children are estranged, and Mrs. Litvak suffers from Alzheimer’s, poor thing. He drops Yakov at a dimly lit house, promising that people will come by at 5:30am to pick up the body. It’s a little before midnight.

An inventory: Yakov is trapped in a dark house, with an unreliable elderly woman, running out of meds, haunted by trauma, wracked with spiritual pain at being back in the community he had to leave. He’s not supposed to contact the outside world. The sun comes up in about five hours.

Like I said, an excellent set up! And from there director Keith Thomas makes the most of deep shadows, creaking floors, unexpected texts, and Yakov’s own terror—not that he’s being haunted by an evil Mazzik, but that he’s losing his mind. Dave Davis is fantastic as reality unravels around him, and he only gets better as you start to understand why he’s such a wreck. The Mazzik itself isn’t seen much, because it doesn’t need to be. It isn’t going to bite you or slash you… at least, not at first. What it does is create a sense of grief and guilt that inexorably crushes your hope, joy, and will to live. It traps you in loops of your worst moments and feeds on your pain. Yakov’s worst moment provides quite a meal for the demon.

There are a few scenes when the film explains its central haunting a little too much, but those aren’t enough to detract from the scariness. The only other weakness is that the movie relies so heavily on hints, shadows, and blurriness, even in scenes that need more light and focus, that I felt like we were seeing some of the budget constraints on screen. But those are very small quibbles with a film that operates as a true horror movie, an examination of trauma and grief, and a look at a fascinating religious practice. Also, and I know I tend to harp on this, but The Vigil sticks the landing in its last few moments! Horror movie endings are always so hard to pull off, but this one, like The Night’s, sends us out on a perfect eerie note.

The Vigil is available to rent or buy on Youtube, Google, Amazon, and Apple.