Number One Fan is about the people we fall in love with who never know our names.

It is 1997 and we are crying while a procession moves the body of Diana, Princess of Wales down the streets of London.

We do not know the princess. We never shook her hand, but we will say that she touched our lives anyway. We’re as close as Sir Elton at his piano, rewriting a song of mourning penned for another blonde we did not know to fit this one. We have lost something.

The feeling of knowing someone who does not know us is referred to as a “parasocial relationship.” When we develop this one-sided relationship, giving it power and importance in our lives, it blossoms into parasocial delusion.

In 1997, it was fully possible to develop a parasocial relationship with a member of the British royal family. In fact, parasociality defines the monarchy for most people who do not live under the direct rule of a prince; they’re just someone you know everything about who’s never once heard your name. People certainly had delusions about Diana Spencer. Donald Trump was famously obsessed with her, bombarding her with thousands of delivered roses and orchids at her Kensington Palace home after her marriage to Prince Charles fell apart. Most obsessives lack the resources to show themselves so plainly.

It is 2008 and we are watching Britney Spears shave her own head on TMZ. We are reading Perez Hilton’s breathless descriptions of her braless and in Uggs at a Los Angeles Rite Aid. We are convinced she should lose custody of her kids, we are relieved when she goes to rehab. And really, it’s so obvious. We watched this kid grow up half-naked on the cover of Rolling Stone. We’ve seen her stoned out of her mind, falling out of a Hummer as paparazzi aim their cameras up her skirt. We’ve watched her champagne-drunkenly grope her backup-dancer-turned-husband on the balcony at the Four Seasons. We’ve seen enough. We know her.

It is 2021 and we know her better. We were wrong. We have been hounding her, and her family has been ruthlessly pimping her for millions of dollars all those years. Her 2008 downward spiral was a human tragedy, not a spectacle. Even Perez Hilton wipes the blood off his mouth. Conservatorship ends, and Britney belongs to herself.

Except she still belongs to us, doesn’t she? Didn’t we make her, unmake her, remake her? Wasn’t she made for us? We’ve been there with her, every step of the way. We know her.

It is 1996 and George R. R. Martin is publishing A Game of Thrones, the first fantasy novel in a series that we will love and nominate for awards. It is 2011 and Martin sees the series adapted into a mega-millions budgeted prestige primetime television series that earns 59 Emmy Award nominations, but that’s all our doing, isn’t it? We were his fans first, following his humble hat and suspenders around begging for the next head to roll for the dynasties of Westeros. We know George; he’s just a regular nerd you see at Worldcon sometimes; he’s sarcastic and silly and always a familiar face. Did you see him at Norwescon? Yeah, me too. He’s one of us.

It is 2012 and we are nervous. Well, we are concerned. George isn’t young, and we notice that he’s fat and we’re worried he might not live to finish the series. And we’ve been with him all this time, we’ve bought all the books. We’ve read his blog posts about the Seahawks, for crying out loud. He owes us. He owes us the conclusion. He owes us more than ever, now that the series is on TV and the non-nerd-normies are into it, too. We’re basically friends, so we can tease him about it a little.

It is 2012 and the comedy song duo Paul & Storm release a song called “Write Like the Wind (George R. R. Martin).” It’s a joke, and we’re allowed to joke about creators. We’re allowed to write parody and criticism and speculation; responding to art is what makes it a joy for people who don’t make it themselves. But it is 2012 and we are tweeting at George directly. We are leaving comments on his blog. We are writing him emails—fan mail, really. He ought to be grateful. We are reminding him that he owes us. We are reminding him that he is mortal. We are asking (so concerned!) about his health. We are eagerly awaiting the books he promised us. We love him, ok? We want what’s best for him: fame and money and glory and adulation. We want to encourage him with our friendly little jibes and constant reminders, because we care.

He does not know who we are.

It is 2015 and agents are looking at the size of an author’s platform. They want to know how accessible the author is, does he do in-person events? Does she use Snapchat? Do they have a newsletter? Is the author a person, or a brand? We get to know them, we get to love them. Do we own them? Maybe a little piece?

It is 2018 and Sarah Gailey is nominated for Hugo Awards as both a fan and as a professional, and the line is blurry. Is Gailey a member of the fan community, one of us geeks like George? We know them; they’re funny on Twitter, telling stories about mimosas spiked with vinegar and sharing pictures of their dog. Except now, we know they’re a big deal. They’re one of us, but their approval and their friendship and their attention and their likes carry so much more weight, because they’ve made it. They’re one of us and they’ve become a legitimate creator. Published writer. Hugo nominee. Their favor is now a social currency, and of course we want it.

We are so many, and they are one. We know Gailey; Gailey doesn’t know us.

Diana is on the run, speeding through a tunnel to get away from the cameras, just for a second, to breathe. Britney is cowering on a stoop, her shaved head in her hands. She’s hitting a car with an umbrella to get us to go away. Martin is listening to us ask about his health and his lifespan, asking about when he will finish, and calmly saying “fuck you.” Gailey is tweeting politely for people to let them live.

Diana was literal royalty; insulated from many kinds of consequences by money and power and bodyguards and castle walls. Britney is a mega-rich megastar, and strong enough to survive it all. Martin is wealthy beyond the dreams of most writers, unimpeachable in stardom and set to inherit the crown forged for Tolkien’s brow. Gailey is a bright new literary talent, rising up in speculative fiction, crossed over the line from fan to fantasy in the blink of a 2018 eye. So they can take it. They’re paid to take it. They’re making money off all our eyeballs and attention, and if we didn’t love them, they would be nothing.

They do not love us back.

Our gaze has only gotten sharper in the decades since Diana in the tunnel. Windows into the life of the individual artist have proliferated by orders of magnitude since Britney on the curb.

It is 2015 and we are demanding to know if Seth Dickinson is queer. It is 2016 and Elena Ferrante is dragged out of obscurity by someone who couldn’t let her be. It is 2020 and we are forcing Becky Albertalli out of the closet because we decided it’s our business who is queer enough. It is 2020 and Lindsay Ellis is explaining to some rando on Twitter that his treasured selfie with her does not amount to a relationship. It is 2022 and authors are on TikTok, unboxing their books and scritching their cats. We know them. We’ve seen their kitchens. We’ve read that book so many times, it’s like we’re old friends.

They still don’t know us. That camera only works one way.

There isn’t a simple answer here. The truth is: the relationship we have with writers and creators is complicated. It’s often intimate without being reciprocal, and that is almost impossible for us meat-creatures to understand. Art is deeply personal; everything we put down is in some fashion a self-portrait. People who read our work feel like they’ve seen us from every angle, felt that image touch them.

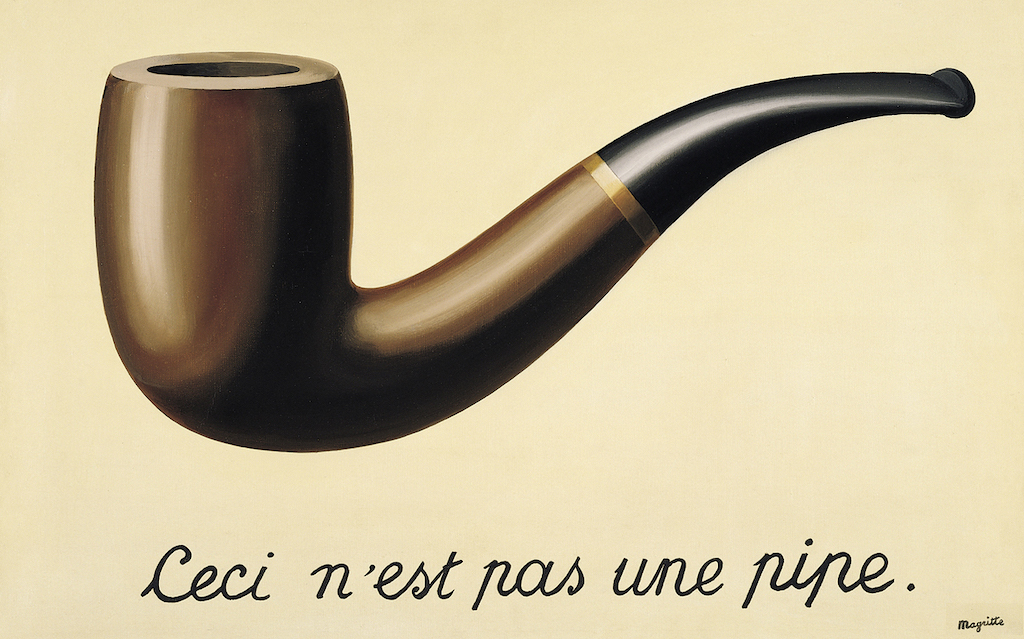

But the artist is not the image. C’est n’est pas une pipe. I’ve wrestled with this cognitive dissonance throughout my career, and I’ve felt it on both sides. I projected my desires on to the writers I wanted to become, and then I felt the projections of others land on me. It’s profound; ecstatic and dehumanizing all in one interaction. Number One Fan gets at the essence of that experience. It sinks the reader deep in the muddy waters of fandom, fiction, publishing, and obsession. I wrote about what it takes, as a creator, to withstand the force of this onslaught of familiarity, entitlement, and misplaced rage.

I wrote about Leonard Lobovich: fan writer-turned-pro, and the object of his obsession: bestseller Eli Grey. They both contend with a market that seeks to know them and tries to consume them. The difference between them is that she knows who she is and how to withstand it.

“Eli wasn’t the healthiest, most well-balanced writer in the world. She drank and she pushed people away from her heart, but she could take the garbage in her inbox and contextualize it properly. She knew that to the people who read her work, she was like the blank screen at the front of a movie theater. She had a starting point and an endpoint and her physical properties that hardly mattered at all. People who read her books could only see what was projected on her. The films and the media and their own expectations splashed all over, and what they had to say in their missives rarely if ever had anything to do with her. They were talking to light and shadow, and she was the unknown surface they forgot was there.

But Leonard. Eli didn’t know everything, but she was sure that there wasn’t enough solidity in his sense of self to take what a frenzied fanbase would dish out. When they waved their hands through the air and caught only light and shadow in their palms, he would see the black eclipse they cast upon him and think they were holes in himself. He’d never be able to take it. He was already too damaged. When his audience turned on him, he had had no inner reserves upon which to live.”

The artist is a person. It’s easy to forget, with all that light and color projected all over them. The story that’s playing out there is making us feel things, and that’s good! It should. But we never touch the screen. If we speak, it does not hear us. The artist is absent from our interaction with the art. The artist is out there somewhere, being human.

Leonard does not know Eli, but he thinks he does. He’s read her work. They’ve seen each other at conventions, they were even nominated in the same year for a big award. But when she wakes up chained in his basement, she doesn’t recognize his face. She does not know him.

Number One Fan is about what happens when parasocial delusion crosses the line from indignance to violence. It’s about who inhabits the voice of the writer, and what social media can do for good and for ill. It’s about who owns art, in an age when IP is licensed, plagiarism is rampant, and even geniuses work for hire. It’s about fandom and control. It’s about the line between fan and professional, and the solution to the very human problem of how to relate to artist and art.

The line isn’t clear. The solution isn’t simple. So I’ll have to tell you a story.

One thought on “Parasocial Delusion: Welcome to the Basement of Your Number One Fan”