From the mid- to late-nineteenth century, a series of discoveries across the sciences made the cosmos seem suddenly to teem with spectral presences. Even the most apparently humdrum dimensions of daily life were now suspected of sheltering invisible worlds. Take color, for instance. Late Victorian advances in spectroscopy, photography, and evolutionary biology made color, and humans’ cognitive experience of it, the subject of heated scientific debate and popular wonder. (The period from the 1850s to the 1930s has been called the “golden age” of color science for this reason.) Among these many revelations, perhaps the most philosophically intriguing to laymen was the mounting evidence that we share our plane of being not just with the visible radiation that we call color, but also with forms of radiation that we cannot see: ultraviolet, infrared, microwave, x-ray.

The more that physicists and chemists learned about the electromagnetic field, the more apparent it seemed that our bodies are under constant assault by forces undetectable by the senses. This seemed an almost supernatural prospect, to some—and literally supernatural, to others. Authors of horror and science fiction were naturally attracted to the narrative possibilities of invisible matter and energy. Stories like Fitz James O’Brien’s “What Was It? A Mystery” (1859), Guy de Maupassant’s “The Horla” (1887), and H.G. Wells’s The Invisible Man (1897) conjured a variety of monsters that hid in plain sight through means paranormal and otherwise. But my focus here will be on three stories that specifically threaded their explorations of invisibility through the eye of color science.

Ambrose Bierce’s “The Damned Thing” (1895), Jack London’s “The Shadow and the Flash” (1903), and H. P. Lovecraft’s “From Beyond” (written in 1920, published in 1934) find fear and sublimity in the seeming paradox of an invisible hue—and in the dizzying opportunities for exploitation and violence that such invisibility might grant the wearer. If the previous essay in my Nightfire series surveyed fiction where color serves as a source of horror, the short stories discussed here do the opposite, treating visible light as our last refuge against existential terror and destruction.

blank text

Ambrose Bierce’s “The Damned Thing” (1895)

Pairing scientific with legal investigation, “The Damned Thing” takes the form of a coroner’s inquest. Someone or something has hideously mauled and killed Hugh Morgan, a frontiersman who lived in relative solitude near an unnamed forest. The only witness to the death, William Harker, claims to have watched Morgan succumb to an invisible foe, a “Damned Thing” detectable only by its howls and its physical impact on the landscape when it moves (grass stirs, light gets blocked). The short story concludes with an excerpt from Morgan’s diary that supports Harker’s account, recording the doomed man’s suspicions that an unseen being has been stalking him for weeks. Rather than chalking this up to a haunting, as a character in a more straightforwardly Gothic tale might do, Morgan develops a scientifically plausible explanation. But the conclusion he draws is no less chilling than a paranormal one would be:

There are sounds we cannot here. At either end of the scale are notes that stir no chord of that imperfect instrument, the human ear …. As with sounds, so with colors. At each end of the solar spectrum the chemist can detect the presence of what are known as ‘actinic’ rays.[1] They represent colors—integral colors in the composition of light—which we are unable to discern. The human eye[’s] range is but a few octaves of the ‘chromatic scale.’ I am not mad; there are colors that we cannot see.

And, God help me! the Damned Thing is of such a color!

Morgan’s mini-treatise on color echoes his era’s interest in sensory thresholds—the premise (still accepted in our own day) that a stimulus must surpass a certain point of intensity “before [it] can gain entrance to the mind,” as psychologist William James wrote. The logical, but potentially disquieting, conclusion that Victorians drew was that humans are surrounded at all times by incalculable realms of stuff too faint for us to perceive. Morgan’s misfortune has been simply to brush up against a being from one such realm. In so doing, he discovers that just because we cannot perceive something does not guarantee that it cannot perceive or harm us.

It’s fitting, then, that Morgan lives on the American frontier, another kind of threshold. Bierce’s choice of setting implicitly pairs the visual unknowability of the material world with the cartographical and animal unknowns of the natural world—the “howling wilderness,” as early white settlers sometimes called them. Indeed, the first invisible beasts that we meet in the story are not the Damned Thing itself, but the ordinary night prowlers that hum and shriek outside the candlelit cabin in which the inquest unfolds:

From the blank darkness outside came in, through the aperture that served for a window, all the ever unfamiliar noises of night in the wilderness—the long nameless note of a distant coyote; the stilly pulsing thrill of tireless insects in trees; strange cries of night birds … and all that mysterious chorus of small sounds that seem always to have been but half heard when they have suddenly ceased, as if conscious of an indiscretion.

The makeshift cabin window here is not unlike the “aperture” of the eye itself: both offer only fleeting glimpses of mostly imperceptible worlds overrun with non-human presences. Rarely does the average person look past the threshold, into those other planes; never does she see the full menagerie of beasts those planes hold. This is, Bierce suggests, a mercy. Despite the trappings of order and power that humans desperately assemble around ourselves—science, the law, the guns the frontiersmen fruitlessly shoot at the Damned Thing—we are in fact wildly vulnerable to the whims of a predominantly non-human planet and cosmos.

[1] Actinic rays are what we now call UV radiation.

blank text

Jack London’s “The Shadow and the Flash” (1903)

If Bierce frames invisible color as evidence of the amorality of the natural world, London uses the same conceit to underscore our own species’ amorality. In “The Shadow and the Flash,” two scientists, bitter rivals since boyhood, race to turn themselves invisible by chemical means. One man, Lloyd, creates a paint so black that it absorbs all rays of light that strike it. Paul, conversely, seeks transparency, and invents an elixir that rearranges his molecules so that light passes straight through him. (The latter approach recalls the refraction experiments by which Griffin becomes the eponymous Invisible Man in Wells’s 1897 novel.) The competitors draw tantalizingly close to their goal, but a small remainder of visible matter persists in each case: a faint shadow periodically reveals Lloyd’s presence, while a flash sometimes betrays Paul’s.

“The Shadow and the Flash” carries forward some of the phenomenological mise-en-abyme of “The Damned Thing”; both stories’ authors clearly still find freshly terrifying the notion that, as Lloyd remarks, “‘[c]olour is a sensation [with] no objective reality.’” But the true focus of London’s later story is the social impunity that an invisible person might enjoy and exploit under invisibility’s cloak. “‘[T]o coat myself with [invisibility] paint would be to put the world at my feet,’” rhapsodizes Lloyd. “‘The secrets of kings and courts would be mine, the machinations of diplomats and politicians, the play of stock-gamblers, the plans of trusts and corporations.’”

But Lloyd and Paul alike fail to achieve anything remotely as grand as these ambitions because they’re too busy trying to kill each other. Prior to the invisibility contest, the vigilance of their loved ones—and little else—keeps the boys from hurting one another or themselves. As teenagers, for instance, the frenemies compete to see who can hold his breath longer at the bottom of a pond. Minutes pass with no sign of the boys, and their nervous companions finally jump in the water to find the pair “clutching tight to the roots [at the bottom], suffering frightful torment, writhing and twisting in the pangs of voluntary suffocation; for neither would let go and acknowledge himself beaten.” Only the forcible intervention of their friends removes Paul and Lloyd from the swimming hole, and from suicide.

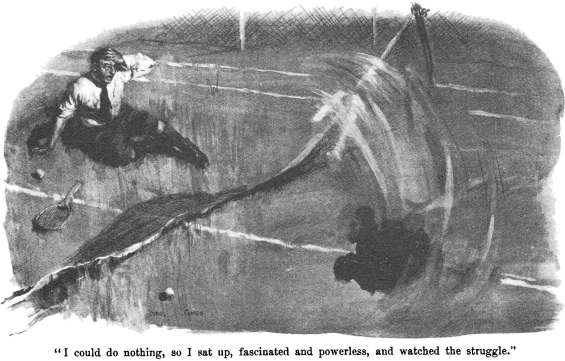

But invisibility, practically speaking, makes any such collective checking of the death drive nigh impossible. Paul and Lloyd approach the asymptote of their quest at the same rate, both eventually becoming unseeable save the occasional flash or shadow. Yet the two scientists’ first impulse, among the sea of marvelous possibilities offered by their new powers, is to fight like crazed animals finally freed of their leashes. In the tale’s final scene, the narrator “hear[s] a snarl as of a wild beast, and an answering snarl,” indicating that his friends Paul and Lloyd both stand before him, unseen. But unlike the incident at the pond, the narrator now can barely see the adversaries, and so is powerless to intervene when they begin to fight. As a result, the opponents quickly battle to the death. London’s implication is that humans tend towards violence, and so only social visibility—the panopticon of mutual witness and accountability—keeps us from utter atavism.

blank text

H.P. Lovecraft’s “From Beyond” (1934)

Impressively, Lovecraft’s story achieves a nihilism still deeper than Bierce’s or London’s. In “Damned Thing,” invisible color horrifies because it lays bare the brutal species that live alongside humankind without our knowing it; “Shadow and the Flash” shows the most brutal species to be humankind itself; “From Beyond” combines these two brutalities with a devastating “Yes, and.”

In Lovecraft’s tale, disturbed scientist Crawford Tillinghast has invented a machine that radically expands humans’ sensory capacities. The device uses electromagnetic waves to stimulate the subject’s pineal gland, allowing him to see, at first, “pale, outré” colors he’s never encountered before, then entire planes of existence not normally perceptible to the human eye and ear.

As Tillinghast demonstrates the technology to the narrator, an old friend, the two men soon gain the capacity to glimpse another, hideous reality superimposed directly upon their own. They can now see an uncountable horde of “great inky, jellyfish monstrosities” that periodically “devour one another, the attacker launching itself at its victim and instantaneously obliterating the latter from sight.” This is all the more alarming because, as Tillinghast notes, once a person begins to perceive these beings, he also risks being perceived by them. The scientist soon confides with sick glee that he recently sacrificed his former servants to the otherworldly organisms in order to save himself from them—and plans to do the same to the narrator.

By unfolding these revelations in tight sequence (a single villain’s-confession monologue), Lovecraft’s story draws an implicit analogy between Tillinghast’s remorseless murder of his servants and the other-dimensional creatures’ remorseless murders of one another. In the purely mechanistic universe that is the “Beyond,” powerful creatures harm weak ones whenever it conveniences them. And if one gazes too long into this dog-eat-dog abyss, as Tillinghast has done, one begins to apply its rules to our own plane of existence.

The radiation machine, in other words, has warped Tillinghast’s ethical, as well as his optical, view of the world. Yet like many a mad scientist before him, Tillinghast regards his own increasingly unscrupulous belief system as a triumph rather than a devolution. As he explains his reasons for inventing the sight-enhancing device, Tillinghast describes an interspecies hierarchy in which greater perceptive capacities mean greater power:

“What do we know… of the world and the universe about us? Our means of receiving impressions are absurdly few, and our notions of surrounding objects infinitely narrow… With five feeble senses we pretend to comprehend the boundlessly complex cosmos, yet other beings with a wider, stronger, or different range of senses might… see very differently the things we see… The waves from [the machine] are waking a thousand sleeping senses in us; senses which we inherit from aeons of evolution from the state of detached electrons to the state of organic humanity.”

By this dreadful logic, humans share a common ancestry—and perhaps a common future—with organisms like the gelatinous abominations of the Beyond. By coupling this premise with Tillinghast’s ruthless murders of his servants, the story implies that the only thing separating humanity from violent anarchy is our relative blindness: cloistered vision also cloisters our virtue. And thank God for that. Because Lovecraft indicates that if we could only see things the way they truly are—if we could peek into the sphere of uncaring matter that lies “beyond” the comforts of ROYGBIV—we would quickly become every bit as apathetically vicious as the “jellyfish monstrosities.”

Ultimately, Lovecraft, London, and Bierce turn the new forms of sight granted by ultraviolet, x-ray, and infrared technologies onto the human soul itself. Their stories hint that if we could gaze into the unseen essence of the universe, and of our own species, we may well find nothing there but indifferent matter.

This post was written for Nightfire in partnership with Pseudopod.

One thought on “Phantom Wavelengths: Three Tales of Invisible Color”