When Bill Landis dropped dead on the streets of Chicago in 2008, it was a bit like a tree falling in the woods: he was gone, but no one could really be certain it’d had an impact.

There were obituaries, sure–a few scant words on a website here, a passing reference to his death on a blog there. He’d written a book about grindhouse theaters; he was some sort of expert on 1980s New York; he’d apparently published some kind of magazine. It was almost as if his importance were passed by osmosis, as though people knew that his passage meant something, though no one was quite certain what that something was.

Tellingly, the greatest tribute paid to him was on the pornographic website Celebrity Skin, where writer Mike “McBeardo” McPadden penned a hilarious and irreverent eulogy recounting his turbulent time as Landis’ boss in the early 2000s, recalling him as a brilliant but troubled film journalist who spent just as much time terrorizing him for paychecks as he did writing content for the site. The comments section quickly devolved into something approximating a roast, as those who’d known and loathed Bill came forward with their own backhanded reminiscences and final potshots at the not-so-dearly departed. They had come to bury Bill, not to praise him. The uninitiated could be forgiven for assuming he was nothing more than a troll of the early internet age, a self-important, foul-tempered weirdo whose primary claim to fame was sending abrasive emails to editors who’d been kind enough to print his work but not quick enough to put the check in the mail.

And that is a terrible shame, because, in an age before the internet, before magazines like Fangoria and Rue Morgue were running articles on social justice and the deeper themes of films like Get Out and Midsommar, before the Boulet Brothers helped codify the fusion of queer culture and horror, before words like “person of color” and “trans” entered the popular lexicon, Landis’ magazine Sleazoid Express helped lay the groundwork for modern genre criticism. At the same time it documented, analyzed, and ultimately preserved subcultures and ways of life that would otherwise have been lost to time, many of which we’re only now beginning to assess, understand, and interrogate.

On paper, Bill Landis was the last person anyone would’ve guessed would go on to found and codify an entirely new school of genre criticism. A military brat born on an Air Force base in France, Landis was a child genius who breezed through school and already had a masters’ degree and job on Wall Street by the time he turned 20. One of the first wave of young professionals to have a background in computer science, he quickly established himself as a hotshot at Merrill Lynch at the dawn of the Reagan Age, the very prototype of the Alex P. Keaton, knit-tie yuppie with his own apartment and savings account before he could legally drink. There was something different about Bill, though—he’d spent his childhood sneaking away from the Greek Mens’ Social Club where his grandfather hung out in the late 60s and early 70s and slipping into the nearby grindhouse theaters on New York’s famed 42nd Street, taking in films like Midnight Cowboy and Blood Feast when most kids his age were still watching Scooby Doo and Johnny Quest. Though his parents regularly took him to Broadway shows and he was a fan of Bergman and Fellini, Landis came of age seeing no distinction between arthouse material like The Seventh Seal and genre fare like Night of the Living Dead; indeed, the way he saw it, there was just as much artistic merit in the material that premiered at Cannes as there was in the low-budget exploitation films being shot in his very own backyard in Manhattan.

When, in 1980, the 21-year-old Landis caught a showing of Doris Wishman’s early trans-rights film Let Me Die a Woman—a 1978 docudrama about a disparate group of trans people seeking gender confirmation surgery—Landis was moved enough by the picture to want to document and analyze it, believing no one else would take the film seriously. Returning to his apartment that night, Landis sat down at a typewriter and birthed the first issue of Sleazoid Express- a magazine dedicated not only to giving serious critical analysis to the grindhouse films of 42nd Street, but also the people who went to see them.

It was a bold move. The Satanic Panic was in full swing and anyone who dressed in black, listened to heavy metal, and wasn’t straight, white, and Christian was considered suspect. Horror films were looked upon as the shibboleth of the damned, denounced from the pulpit and on the six o’clock news as a common language for freaks and killers. Gene Siskel publicized the home address of Betsy Palmer so people could shame her for appearing in Friday the 13th; Fangoria editor Tony Timpone appeared on daytime talk shows to defend the genre against accusations it was literally rotting kids’ minds. Even among its own fans, horror and exploitation cinema were rarely taken as anything more serious than an escape. Fangoria had just begun publication and functioned primarily as something of a precursor to the internet, primarily concerned with providing readers behind-the-scenes-photos, news on upcoming releases, and special effects tutorials. The only other major horror publication at the time—Famous Monsters of Filmland—was pure nostalgia fuel, filled with loving anecdotes and tales about the golden age of fright films. Critical analysis and an exploration of deeper themes weren’t anywhere on the radar.

Not so with Sleazoid. Where other writers looked at horror films and saw blood, scares, and a good time, Bill Landis saw art. Part movie magazine, part anthropological journal, Landis’ mandate was as complex as it was deceptively simple: he was going to write about 42nd Street. Over the course of the next five years, Sleazoid Express provided its dedicated readers—whose number came to include Larry McMurtry and even Roger Ebert himself—with a you-are-there, fly-on-the-wall, gonzo travelogue of 42nd Street, the movies that played there, and the people who watched them. For Bill Landis, the Deuce was an artful kingdom of the damned where everyone was equally unequal; it was a place where Black and trans and Latinx and queer people could gravitate to see films that reflected their lived experience, oftentimes made by individuals of a similar background who couldn’t get a fair shake from Hollywood. Decades before Patty Jenkins or Jordan Peele or Luca Guadagnino, there was Roberta Findlay and Rudy Ray Moore and Andy Milligan, and Bill Landis wrote about them and their fans with the same love, reverence, and respect afforded to Scorsese or Spielberg. Picking up an issue of Sleazoid Express was like entering an entirely new world, with Bill—or “Mr. Sleazoid” as he called himself—as their delightfully demented guide. Readers were just as likely to get a serious critique of Videodrome as they were to get a blow-by-blow of a fistfight that’d taken place in the theater balcony; as the decade wore on, Bill interviewed and preserved the experiences of 42nd Street sex workers and hustlers as they and their friends slowly fell prey to the AIDS and crack epidemics of the mid-80s, given space to tell their stories when the president himself had written them off as lost causes.

As noble as his imperative may have been, Bill’s life as was just as messy as the plot of one of his beloved exploitation films. Behind the sensationalism of Sleazoid Express was real, human pain; a survivor of childhood sexual abuse, he fell too easily into the 80s NYC drug scene, discovering that cocaine and heroin were potent ways to numb his emotional trauma. The line blurred between Bill and the “Mr. Sleazoid” persona. The magazine—and Bill—burned out in 1985, after narcotics came to dominate his life; the next year, his then-girlfriend Michelle Clifford helped him get clean before the pair wed, and he spent the next decade and a half in quiet domesticity, briefly emerging from obscurity to pen a biography on cult filmmaker Ken Anger. In the early 2000s, Landis and Clifford relaunched Sleazoid and wrote a book version of the magazine published by Simon and Schuster, briefly making them the elder statesmen and impresarios of the burgeoning grindhouse boom brought about by Kill Bill, House of 1000 Corpses, and their ilk. The pair gave speeches at Alamo Drafthouses and film festivals and lent their personal experiences to a new generation of cinephiles.

It should have been the dawn of a new chapter for Bill, but the success was short lived. He relapsed, now having access to the potent opioids that ravaged the country from the Bush era on. Within three years of the Sleazoid book’s publication, Bill’s life fell apart. He became totally dependent on drugs, giving birth to the horror stories about him that would later be recounted after his demise. The goodwill his 21st century work had garnered was quickly squandered, and he burned bridge after bridge before dying of a drug-induced heart attack at the age of 49.

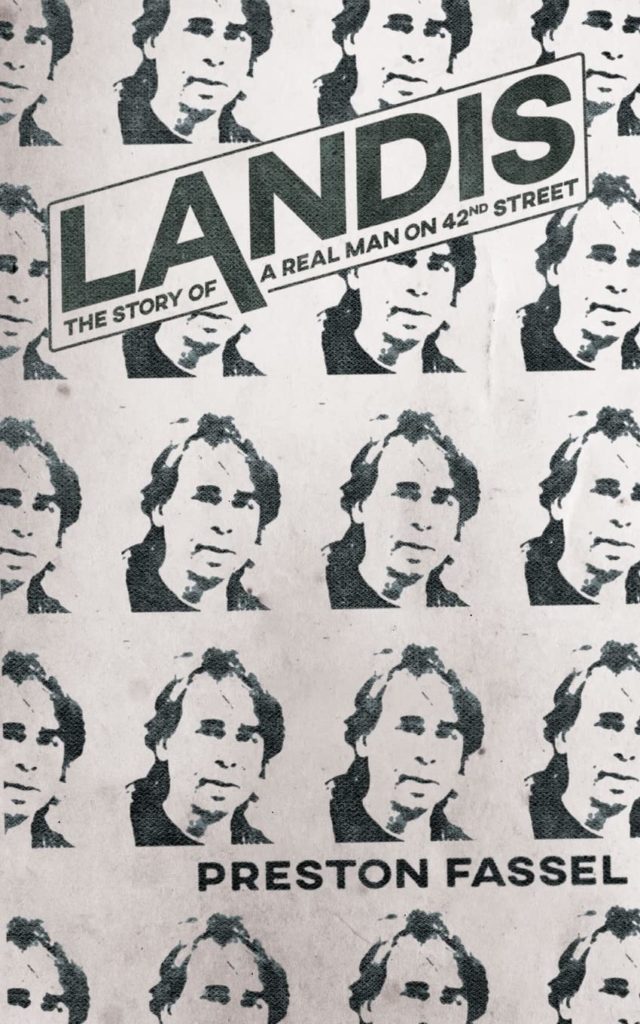

For those who only knew him late in life, it’s easy to remember Bill only in negative terms—drug addict, junkie, harasser. The phrase “cartoon character” has often been used to describe his final years by friends and enemies alike. Beyond the addiction, though, beyond the pain and trauma and absurd anecdotes, there was a real, complicated, human being. Without Sleazoid Express, there’d be no modern iteration of Fangoria, no Rue Morgue or Diabolique or birth.movies.death; without Bill Landis, the entire culture of genre film consumption and criticism that’s grown up around Alamo Drafthouse and AFGA, Arrow Video and Severin and Vinegar Syndrome, would be nonexistent. He was a pioneer and a scholar; he was a husband and a father; he was a real man; and that’s the iteration of Bill Landis I sought to document and preserve in Landis: The Story of a Real Man on 42nd Street.

As one of the many writers his work inspired, I wanted to tell his story—not the story of Mr. Sleazoid but of Bill Landis the human being, who gave so much to the world. There’s sensationalism, yes—you can’t talk about Bill without discussing his drug use, his time as an adult film star under the nom de porn Bobby Spector, the period of his life he worked as a male hustler, or his final years as the ersatz den father to a Dominican drug cartel in Washington Heights. More than that though, there’s life and there’s love—the life Bill led, the love he had for the exploitation films of 1980s Times Square and the people who watched them, and the love I have for him for all he gave to the world, and to me. With Landis: The Story of a Real Man on 42nd Street out this month, I hope you’ll give it a look; and I hope that I’ve done due justice to a man who laid the groundwork for the way we watch, think about, and assess genre cinema today.

Thank you for this work. I knew Bill briefly during the “domesticity” phase. He was such a fascinating and magnetic person. I’m glad his the story of his life and work are being preserved.