To celebrate the release of the second season of Come Join Us By The Fire, our audio horror anthology, we’ve asked authors with stories included in this year’s anthology to join us and write about horror. Below, Shaun Hamill, whose story “Music of the Abyss” you can listen to here, writes a requiem for a Walkman and tells us how he found himself in his fiction.

THE DISCLAIMERS

THE DISCLAIMERS

THE DISCLAIMERS

When team at Tor Nightfire accepted “Music of the Abyss” for inclusion in this year’s Come Join Us by the Fire anthology, they invited me to write an essay to accompany the story. They threw out a few different ideas for the piece: maybe I could talk about the genesis of the story, or provide some tips and tricks for writing horror. I’m not a strong essayist (I specialize in made-up nonsense and daydreams, so coherence is usually the last thing I wrangle from a story), but after several drafts of meandering prose and earnest effort, I’ve ended up with a hybrid of those two options. Sort of a “how-to” by way of “how I did.”

I’ll issue a couple of warnings up front. First, this essay contains some spoilers for “Music of the Abyss.” And second, I doubt my advice is going to knock your socks off. Like most good craft advice, it sounds “no duh” in theory, but the execution is almost always more complicated than it looks.

THE CRAFT ADVICE, PART 1

Fantasy and its goth sister, horror, are my favorite genres of fiction. I love the trappings of both—the high adventure, swords, and magic of the former, and the foggy moors, rattling chains, and dark wonder of the latter. But what I love most about them are the ways in which they allow us to literalize our daydreams and wishes, our anxieties and fears, and to address them directly. The best genre fiction happens when authors wrestle with their own deepest concerns. It’s not so much “write what you know” as it is “write what you fear.”

The trick is how to do it, right? It seems to be a two-fold process. The first part has to do with your subconscious.

In Zen and the Art of Writing, Ray Bradbury posits that you don’t need to worry about putting themes into your work. What you care about will manifest in your fiction, one way or another. This is true for some writers, like Bradbury, or like Stephen King, who claims he wrote The Shining without an inkling that he was writing about his own struggle with alcoholism. This sort of writing-as-discovery has always been true for me. For example, it wasn’t until the tenth or eleventh draft of my novel A Cosmology of Monsters that I noticed my protagonist, Noah Turner, spends a lot of the book wearing masks, and I realize now that I didn’t understand my own main character until that moment.

The second part, though, is the part you can control and train yourself for. This is the part I call “the emotional autobiography.”

SOME ACTUAL AUTOBIOGRAPHY

When I wrote A Cosmology of Monsters, I spent a lot of time thinking about my childhood and adolescence, and asking my parents what they could remember. One thing that came of those conversations was my father reminding me of my one-time obsession with music.

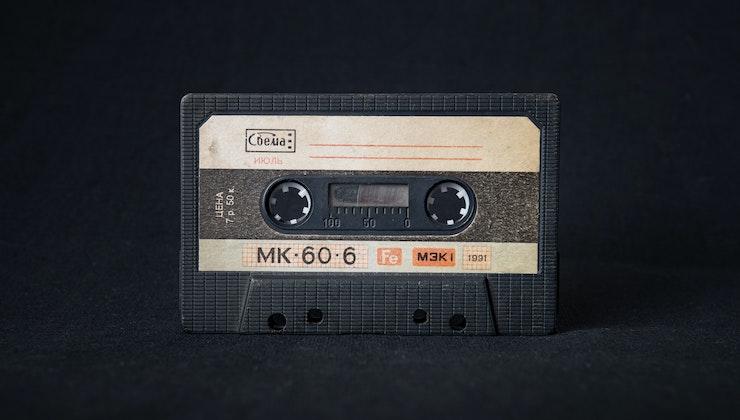

I had a pretty rough childhood. I had two parents with bipolar disorder, both of whom were regularly in and out of psychiatric facilities. My father attempted suicide when I was 11, and after my parents’ divorce, my mom and I were constantly on the brink of financial ruin. I coped with the never-ending anxiety (and occasional hungry days and nights) by reading a lot of books, and with my Walkman. It went everywhere with me, and paid the price for constant use. When the battery door broke, I taped the AAs in place. Same for the feeble band of the headphones, which I delicately repaired again and again with a roll of scotch tape. When the belt clip snapped off, I carried the player around in one hand (or in a jacket pocket if it was cold). When the wires on the headphones started to fail, I endured only getting sound in one ear until l could talk my parents into buying me a new pair. I lived inside my terribly unhip music—movie soundtracks, John Williams scores, and later, things I taped off top 40 radio––it gave my daydreams a pulse and a shape, made them more potent. It was where I went to work through the stories I would someday write, the love affairs I would have as a grownup, and the adventures I would go on if my circumstances were only a little different. It was a portable escape hatch, or, if you prefer, a wall I could erect between myself and the world.

I was so desperate to keep the music playing at all hours, that, if my batteries died and there weren’t any more in the house, I would walk to the convenience store down the street to buy more. No matter the time of day or night, I would walk through my poor, rough neighborhood to the 7-eleven and buy the biggest pack I could afford (usually just a four-pack). This went on for years, even (or especially) after I graduated to a Discman in high school. I was such a regular fixture at the store that the night cashier came to recognize me, and once even ventured the friendly comment “You sure do like batteries.”

To which I, with cunning wit (and a staggering lack of eye contact), replied, “Yep.”

THE CRAFT ADVICE, PART 2

When Dad reminded me of all of this, he suggested that I might find a place for it in Cosmology. I couldn’t, but the image, and the intense melancholy that surrounded it—the boy I had been, so poor, so worried, so desperate to keep the music going—wouldn’t leave me alone. Since I had just finished a novel about cosmic horror, it’s no surprise that my imagination found a way to marry the image and the genre. To show me a boy who, through the circumstances of birth and community, was very near to surrendering his own hard-won music forever. The entire story flowed (sorry, sorry, I know, roll your eyes) from that central concern.

The most effective fiction I write—the pieces that sell, that don’t end up in a drawer or an old hard drive or drifting somewhere in the cloud—all contain an element of emotional autobiography. When I’m writing about monsters from worlds beyond our own, I’m writing about my fractured childhood and the probably all-too-common mix of shame and desire that accompanied my own sexual awakening. When I’m writing about suburban magic users, I’m writing about the complications that arise from lifelong friendships. When I write about fish people slaughtering humans in order to descend and join the deep ones beneath the waves, I’m writing about the desperation of a kid who has one escape from the awfulness of his circumstances—an escape that could be taken from him at any time. Pain, fear, desire, memory—these are the wells I draw from to create fiction that (hopefully) bites back at the reader just a little. It sounds easy, right? But it’s taken me nearly forty years to figure out how to find and use it with any effectiveness.

Shaun Hamill grew up in Arlington, Texas, surviving mainly on a steady diet of horror fiction and monster movies. He got his bachelor’s degree in English from the University of Texas at Arlington in 2008, and his MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in 2016. His debut novel, A Cosmology of Monsters, is on shelves now. He currently lives in the dark woods of Alabama with his wife, his in-laws, and his dog.

Listen to Shaun’s story “Music of the Abyss” on Google Play here, and listen the the entirety of the second season of Come Join Us By The Fire here.