In the afterword to Ray Bradbury’s From the Dust Returned, he writes about the memory of being seven years old and getting roped into decorating his family’s house for a Halloween party. Tucked up in an attic to spook the new arrivals (who, it seems, had to come into the party through a complicated climb-then-slide situation that deeply appeals to me), he tells us that he had the first inklings of wanting to write about “the idea of this Family who were most strange, outré, rococo.”

I myself grew up in a big sprawling Victorian with a good-witch mother and a do-anything father and a sister whose imagination only pushed mine further. We went all-out for the holidays, but the autumnal ones remain particularly vivid in my memory. I remember peering through the iron grates in the floor of my parents’ bedroom (where my sister and I were watching Mary-Kate-and-Ashley videos rented from Blockbuster) to see robots and vampires and witches and punny costumes whose jokes would only make sense to me years later; I recall the house being full to bursting with family and friends gathered for a Thanksgiving feast. Magical things happened in my house, even if I didn’t yet understand them, and my mind was irrevocably changed by the possibilities.

I share this to help explain why Bradbury’s late fix-up of a novel, compiling stories from over 50 years of his career into a narrative, has always been a dark horse contender for my favorite book. It is the story of a family, a strange and unusual one––a family like I imagined mine to be. When I first read this book, my grandmother lived on the top floor of our house and to this day I still thrill at the way Bradbury’s first chapter captures the eagerness and small fears of a young boy going to talk to his grandmother, to ask her to tell him about the family soon to gather for a grand reunion. Admittedly, my grandmother’s tales could not match those told by this boy Timothy’s grandmother––who is his “A Thousand Times Great-Grandmérè,” to be exact, and who demands a drop of B.C.-vintage wine before she can begin her telling.

Apple | Bookshop.org | Amazon | Barnes & Noble | IndieBound

Even if you’ve never heard of From the Dust Returned, you may have met members of the Elliott family in some of Bradbury’s other work: “Homecoming,” the centerpiece story, is one of his earliest, first published in 1946 (in Mademoiselle, of all places) and then collected in several of his most famous books, including Dark Carnival and The October Country. “Uncle Einar,” “The Traveler,” “West of October,” “On the Orient North,” and “The Wandering Witch” (originally published as “The April Witch”) all revisit the family and appear throughout The October Country and The Toynbee Convector. These stories, by and large the longest and arguably some of the best in Dust, provide the poles for Bradbury’s big family tent, which he then fills with a matriarch older than the Sphinx, an invisible cousin, a cat and a spider and a mouse, and many other dark dreamings besides.

It would be easy for a reader already familiar with those famous stories to write this book off, as they might a Marvel movie being brought back into theaters because a few deleted scenes were added into the cut. And Bradbury does pad the page-count with a dozen flash-fiction-length chapters as well as twenty or so small sketched icons centered on otherwise blank pages. But to dismiss the book as a retread is to miss the point: this book is a career-spanning passion project for Bradbury, and one born out of a fantastic piece of trivia.

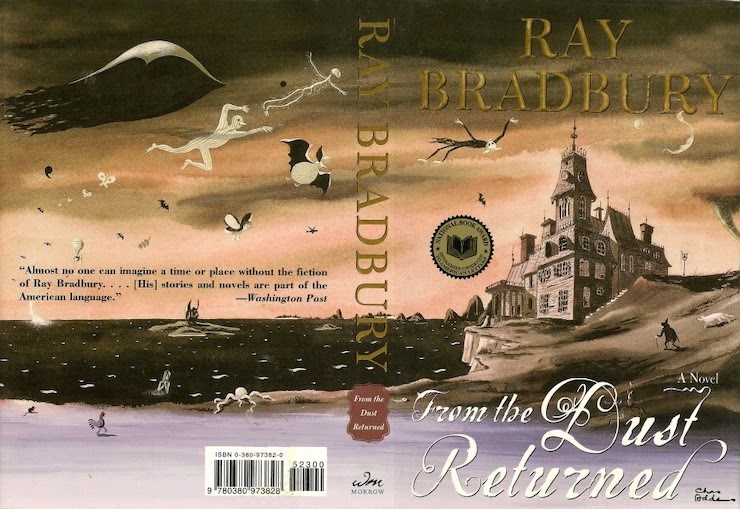

When Bradbury published “Homecoming” in Mademoiselle, none other than Charles Addams drew the illustration. (Addams’ drawing of a towering Victorian perched on a hill with all manner of frights winging their way home graced the hardcover of From the Dust Returned.) In fact, the collaboration between these two October giants was originally intended to be more than a one-off. They were fans of one another and agreed to work on a series of stories that Bradbury would write and Addams would illustrate, all about this creepy, kooky Elliott family. Life (and, apparently, Bradbury’s work on John Huston’s film adaptation of Moby-Dick) got in the way and Bradbury never found the time, so Addams went on to create his eponymous family and Bradbury created his Elliotts. (Or so Bradbury tells it, although the timing of that tale is a bit suspect: Addams already had his family running rampant in the pages of The New Yorker by the time they worked together on “Homecoming,” but the myth is more entertaining to me than the reality.)

For a long time, I only thought about this book in the way that Bradbury originally pitched it to Addams in 1948: “It will become a sort of Christmas Carol idea, Halloween after Halloween people will buy the book, just as they buy the Carol, to read at the fireplace with lights low. Halloween is the time of year for storytelling.” But re-reading the book in full this month, this year, I found it resonating differently than ever before. There is, yes, something very 2020 about the character of Cecy, astrally projecting herself into other humans (as well as animals) to see the world while her body rests at home in a sort of self-imposed quarantine. And I did take great vicarious delight at seeing a sprawling, strange family coming together for the holidays in a year when many of us won’t be able to do the same.

But more than that––or perhaps inevitably building off of those things, off of the ways in which we cannot avoid the realities around us even if we want to––I was moved by the trick of the ending. It might be Bradbury’s best trick and it isn’t a new one to this collection, but I don’t know that he’s ever done it better: he turns a story into an existential manifesto, a memento mori that doesn’t just remind us that we will die but serves instead a simultaneous paean to time that’s passed and a hopeful springing towards the time to come.

After the great Homecoming has dispersed (to meet again, they tell us, in Salem in 2009! Oh, that Bradbury might’ve lived to write that next reunion!), the Elliott Family continues to try to fit into a world that is resistant to their strange charms. They weather the spectres of war and the march of progress, they raise children, they fall in love, they grapple with their identities as any of us might do… and then a black sheep relative, enraged at not getting his way, poisons the townspeople against the family. From there, it is no surprise that the culmination of the novel arrives with torches and pitchforks.

But the family survives. Even as the townspeople descend on the house, A Thousand Times Great-Grandmérè comforts Timothy, the foundling human boy that the Elliotts raised as one of their own. He tells her that he might want to live an ordinary life instead of a strange one, that “some nights I wake up and cry because I realize that you have all this time, all these years, but there doesn’t seem to be much that’s very happy that came of it all.”

“Ah, yes, Time is a burden,” she replies. But, she tells him, “the best thing to do in your new wisdom is live your life to the fullest, enjoy every moment, and lay yourself down, many years from now, happily realizing that you’ve filled every moment, every hour, every year of your life and that you are much loved by the Family.”

He agrees to carry her forward, this matriarch of matriarchs, to a place where she will be safe while the family goes to ground — and so he takes her to a museum, where the curator is astonished by this young man and the millennia of knowledge he brings with him. Bradbury leaves it unclear to the reader if Timothy has a body in this box he brings or if A Thousand Times Great-Grandmérè has somehow transmuted into a pile of papers, a book of the dead bearing the tales of the billions who’ve died up til now and the legacy of those who haven’t. Either way, Timothy brings a story, told to him and that he has now joined in the telling. Timothy tells the curator at the novel’s end that if you listen closely, she is still speaking it.

You can try to hear it yourself, if you’d like.

“Come close. No, closer.

Listen.”

What magic, indeed.