Every autumn, when the nights turn cool and the leaves shudder from the trees, I get a little nostalgic. Beers in the backyard twilight beneath the sycamore, our neighbor’s radio playing. It’s something in the air—that sudden bite that tastes like a Friday night when I was fifteen and spitting notes badly through a silver trumpet in the upper bleachers of a high school football stadium.

The truth? I hated Friday night football games. So many halftimes spent under glaring lights on the fifty-yard line, sweating in a goofy hat, pretending I could play a tune and march at the same time. And yet: every fall, this weird waxing for an evening in a crowd. The wind blows a little and the brain floods with dopamine and I’m fooled, once again, into thinking life was better than it was—or, God help me, into wishing it could be that way again.

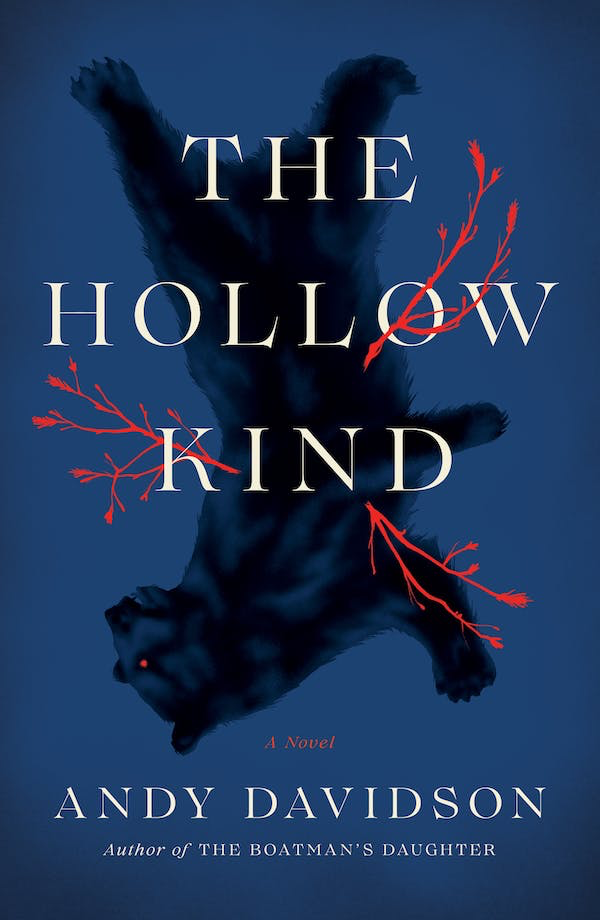

I resisted this feeling, chapter after chapter, when writing The Hollow Kind. Eleven-year-old Max and his mother Nellie are on the run from a monster, and I wanted to remember 1989 as they would have remembered it. A frantic jumble of action figures and notebooks and art supplies thrown into a laundry basket and tossed in the back of a pickup, as if Max’s childhood were still a thing his mother could salvage. The click of a seatbelt. The screech of rubber on blacktop as Nellie’s pickup tore away from their past. In horror, childhood is so often an endless well brimming with demons, isn’t it? Wicked carousels in midnight carnivals. Tattooed preachers wielding switchblades. Hungry clowns offering balloons from storm drains. In IT, there’s a reason adult Bill, Beverly, Ben, Richie, Eddie, Mike, and Stan forget what happened to them in the summer of 1955. Now, as a reluctant member of that grownup club, I get it. It’s got nothing to do with some cosmic monster’s spell. It’s pure old-fashioned trauma.

What sorts of horrors have you forgotten? What bad things rear up from the bedrooms and backyard sheds where you grew up?

I sat down to write this book in the summer of 2020. I wanted to write about a boy, eleven years old, on the cusp of some forever change. That’s the age, isn’t it? Maybe it’s 1977 and you’ve just seen Star Wars for the first time and your world explodes like the whole of space stretching into lightspeed, or it’s 1989 and Batman’s just dropped through a skylight on TV and you realize, my God, that is Michael Keaton! Maybe you’re picking up a paint brush for the first time and touching it to a blank canvas. Or having your first kiss. Or being denied that kiss. Maybe a big kid spits in your face at lunch. Or you find your dad’s Playboy tucked in a drawer. Or you catch your mom crying at the sink in a slant of sunlight. For better or worse, the world catches fire, and you’re never the same. I tried to remember what that was like, that precious, vulnerable time before we Know. Before we Understand. Before we start looking backward, instead of forward. Which is not nostalgia. Nostalgia is not a conscious act of trying to remember, it’s an ambush. To truly remember what it was like to be eleven? This is an act more akin to conjuring. A summoning. Because the past—the true past—it’s a haunting. And the ghosts are always with us.

I grew up a happy kid, mostly. Ate too many Fudge Rounds, for sure. Faked sick a few times to get out of school. Got bullied, like Max. I was nine when a boy put his hands around my throat on the playground, but unlike Max, I was not made to feel weak for letting it happen. I was loved and encouraged by my parents, and I loved them in return. The kind of trauma Max Gardner endures in The Hollow Kind was not my own. Still, my ghosts showed up, every now and then, while I was writing, drawing me down the long summer corridor of 1989, when I, too, was eleven years old.

Here’s a story from that summer: one day, I followed my grandfather into the woods. I sat beside him on a fallen tree in the silence of a pine forest, a shotgun across my thighs. I wore his orange cap, too big for my head. He wore no hat, carried no gun. Just smoked a cigarette and waited out this urge I had to shoot something. Too many Rambo movies, maybe. Eventually, he tacked a paper plate on a tree and I fired a few shells at it. Then, ears ringing, cordite stinging my nose, we headed back. I was happy. The end.

Except it’s never the end with memory. Memories give way to more memories, locked doors fly open, and the ghosts stream out. I remember, for instance, my grandfather’s kind smile, his uncommon warmth. I never saw him angry, though I knew he was capable of great violence. He’d been in the Pacific theatre, had once told me a story about severed heads on Iwo Jima and laughed, gently, afterward. By the time I was playing trumpet in senior band, Mom had told me other stories. How he once struck a cow between the eyes with a Coke bottle and felled her with one blow. How he might swerve his pickup to crunch a stray turtle beneath his tire. Or how, much later, around the time I left for college, a stray black and tan mongrel came around my grandparents’ yard and wouldn’t leave, so my grandfather led her into the woods and shot her. Months later, she came back, tail wagging. You could roll your thumb over a pebble of shot lodged above her left eye. Years later, not long before cancer took my grandfather, the dog died peacefully in the red dust beneath my grandparents’ mobile home. Her name was Dog.

Which is a ghost I summoned, just now. I only just remembered her name. Read The Hollow Kind and you’ll know why that’s remarkable. You’ll say, oh yeah, sure, you wrote that whole book without remembering your grandfather named his dog Dog. Come on. But it’s true. And maybe that’s the real horror of nostalgia. It springs on us with the sudden, overwhelming certainty that things were right, once upon a time, but when we dig down below the surface, down where the memories branch and run like the tangled roots they are, we’re bound to find that darker, sadder truth we’ve forgotten. It’s always been there. We just didn’t see it.

I believe we’re dipped in loneliness the moment we’re born. Hoisted by an ankle, we make our first outraged shriek against being dragged into this sad, ever-turning world, and for the rest of our days, we live with the certainty that something’s missing. Maybe faith gives us strength. Maybe we lean on cynicism. Or maybe nostalgia does its part, too, protecting us from whatever loneliness is—call it our separation from the divine, or living absent a benevolent hand. Maybe some days, the lie is good enough. As a handful of autumn leaves skitter over asphalt, or the fading sun strikes the treetops just so, we bask, momentarily, in that wistful, golden feeling. It comes on like a prayer: oh please, let the light cling just a little longer. Even as the trees become teeth, and the blue above us turns to black.

One thought on “The Horror of Nostalgia: Chasing Ghosts in The Hollow Kind”