I was a pulp horror fan as far back as I can remember. One of my happiest memories is of a school read-in, when the girls in my class sat in a circle on the floor with what seemed to be the complete works of R.L. Stine piled between us, so whoever finished her book could simply throw it back and grab a fresh one. I couldn’t, today, describe for you the plot of a single Fear Street book, but certain images have stayed fresh in my mind: a skull with a two-headed snake inside, a locker-room shower hot enough to scald flesh. These stories both frightened me and filled me with a strange, giggly delight, a feeling I’d recognize in later years when I was finally tall enough to go on the good roller coasters.

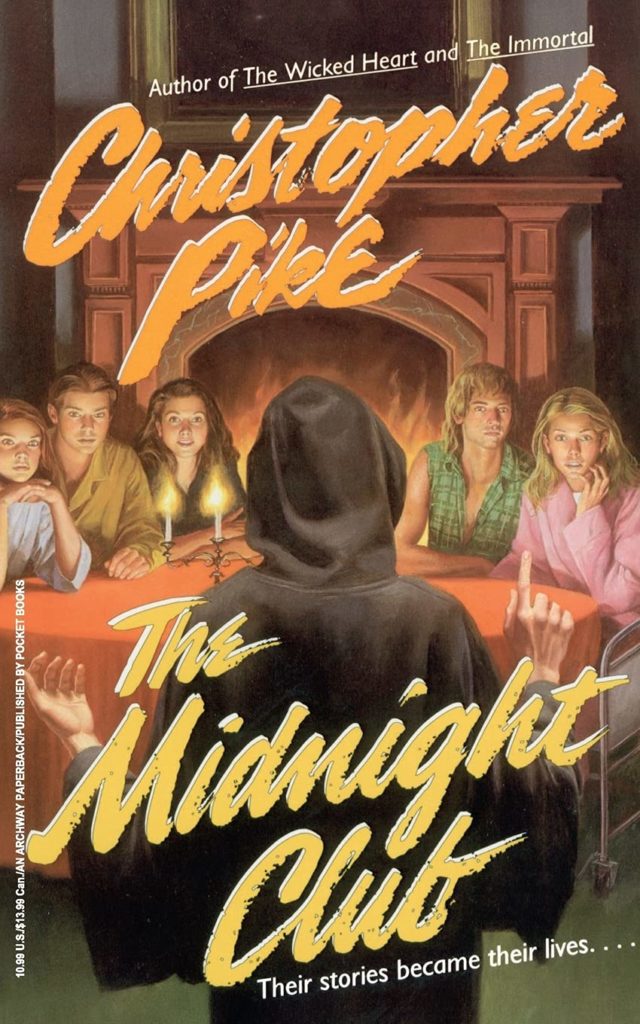

After exhausting the Stine catalogue, the next step was Christopher Pike. Pike’s books were aesthetically familiar: neon-scrawled titles, gasping blondes menaced by skeletal figures. But Pike was gorier than Stine, and also much sexier. Like Fear Street, the details of Pike’s books blur in my memory, but I remember the hammer in The Wicked Heart; I remember (because it made me blush) a sex scene from The Last Vampire. I remember looking up “herpes” in the dictionary after reading Gimme a Kiss. And I remember Spence.

Spence is one of five terminally ill teenagers in The Midnight Club, a book you’ve probably heard of now, if you didn’t read it as a fifth-grader in the ‘90s, because Mike Flanagan made it into a Netflix series. In the show as in the novel, a group of young people living out their final days in hospice care meet every night at the eponymous hour to tell each other stories. While most of the kids have assorted cancer diagnoses, Spence–the lone gay character in the original novel, although not the only one in the Netflix show–is dying of AIDS.

The Midnight Club is a strange book. While Christopher Pike was a horror writer, a thread of esoteric spirituality winds through many of his works. In addition to vampires and serial killers and witches, he is concerned with reincarnation, with Gods and demons, with the fundamental nature of the human soul. And despite the hooded skeleton on the cover of The Midnight Club (that skeleton had an ironclad contract), the book is not really scary at all. Rather, it is a deep dive into these recurring themes. The protagonist, Ilonka, tells stories she believes are from her past lives, in which different versions of herself encounter different versions of the boy she loves, and they hurt and forgive each other over and over again.

Spence doesn’t buy any of that shit. Spence is very sick and very angry. The stories he tells aren’t inspired by his past lives, nor are they resonant with themes of guilt and redemption. Spence tells gnarly stories about fucked-up people seeking bloody revenge. While Ilonka’s characters grapple with their choices and the unintended suffering they cause over the span of lifetimes, Spence’s stories blow all those concerns away in a red mist of catharsis.

Unlike his counterpart in the Netflix adaptation, the Spence of the novel is closeted and hides his AIDS diagnosis from his friends, claiming to have brain cancer instead. Because the novel is deeply concerned with questions of guilt and redemption, Spence is being eaten alive not just by the virus ravaging his immune system, but by the belief that he caused the death of his boyfriend Carl, the first and last love of his short life. As Ilonka points out, there’s no way to know which of them was infected first, but Spence is unshakably convinced of his own culpability. Neither Spence nor Carl’s family life is ever mentioned, but I know things now that I didn’t in elementary school about gay boys dying of AIDS in the ’90s. It’s very plausible that Spence is the only person left who remembers Carl with any kind of affection, the only person who mourns him. Perhaps this is one of many sparks to Spence’s rage: the knowledge that Carl’s memory will die with him, and soon. And this Spence–this furious lonely dying boy, poisoned by shame and self-loathing, telling terrible stories to vent the terrible feelings in his heart–this boy was the first gay character I ever remember reading about.

I’m not sure I even knew what AIDS was, at ten years old. I’m certain I didn’t know yet that I was queer myself. There weren’t a lot of queer characters in children’s books, in the ’90s. I had no context with which to understand the scope of Spence’s pain and regret. But what I did understand, what stayed with me, so ingrained in my memory that I didn’t even need to look up the line to write this essay, was Spence explaining why he pretended to be straight and hid his diagnosis from Ilonka: “In my school, fags were fags, they weren’t people. And I wanted to be a person. I am a person.”

Christopher Pike did not, and I say this with all the love in my heart, excel at writing full-fleshed, well-rounded characters. Most of the teenagers that populate his stories are primarily vehicles for the themes he wants to explore, and Spence is no exception. Spence would probably not be considered great queer representation today. His defining character traits are that he’s dying of AIDS and that he hates himself. And yet this happened to be the character I stumbled upon when I was too young to even be looking for it: a kid full of rage and shame, insisting on his humanity even as his body fails him, still demanding we see him as a person.

In this year’s small-screen adaptation of The Midnight Club, Mike Flanagan and Leah Fong have taken the framing story in a very different direction, abandoning the focus on past lives in favor of a new mystery involving ghosts, miracle cures, and human sacrifice. This plotline doesn’t find any kind of satisfying resolution in the first season’s ten episodes, but to be honest, I don’t care about that very much. I’m not watching to find out what secrets the hospice director is hiding (although it’s great to see Heather Langenkamp again). What fascinates me is these doomed children, the stories they tell, their urge to create in the face of destruction.

In the Netflix adaptation, some of Spence’s roughness is smoothed out, made more palatable for a contemporary audience. He’s no longer closeted, though he does still struggle with shame and fear surrounding his diagnosis, panicking when he accidentally cuts his finger because he’s terrified of exposing the other patients to his blood. He no longer bears the guilt of having infected his boyfriend; instead he talks about forgiving the boy who infected him. We still see Spence’s anger, as when he confronts devout Christian Sandra about the harm done to him in the name of her faith, but he no longer tells stories of nihilistic gore.

This new iteration of Spence even has gay friends: Cheri, an underdeveloped hospice patient with a penchant for lying, and Mark, a hospice nurse who takes Spence under his wing. If the subplot involving Spence reconciling with his homophobic mother feels a bit unearned, perhaps it’s worth it to see the web of connections surrounding Spence, for good and ill. This Spence is more than just a carrier for heady ideas about guilt and redemption. He has a past, a context, a community. Although he never says the line that his predecessor burned into my memory, this Spence asserts his personhood with every action.

2022 is a good year to be a queer horror fan. LGBTQ characters are more visible in the genre than they’ve ever been before; I haven’t even gotten around to watching half the queer horror that came out this year, a statement that would have been unthinkable to me as a teenager. I’m especially delighted to see gay characters in nostalgic tributes like The Midnight Club and the extremely sapphic 2021 Fear Street trilogy, also on Netflix. Although some decry queer inclusion as pandering or irrelevant to the story, it feels to me like an acknowledgment of the reality that queer people have always found, or made, a place for ourselves in horror.

Representation politics is complicated, and often irrelevant to whether a given work of art is actually any good. Still, it matters on a level that is difficult to articulate. I seek out queer stories in every medium and every genre, because some facet of me feels safer when I know that the creator looks at the world and sees me, or people like me, in it. Humans want to recognize ourselves in art, in movies, in film; to imagine ourselves in lives we’ve never lived and might not even want to. This subtext of The Midnight Club becomes much more clear in the translation from text to film, as each character plays the protagonist–or in some cases the villain–of their own story. Here, fiction isn’t necessarily aspirational or hopeful; sometimes it’s an expression of deep fear or grief or rage. In the face of approaching death, Ilonka and Spence and their friends cling to these things, too, because they’re all part of what it means to be alive.

Seeing a well-rounded gay character like Spence–and ancillary gay characters like Mark and Cheri–in a new iteration of a story I loved as a child is life-affirming in a way the members of the Midnight Club might well understand. I want us to be seen, in all our hope and joy, our pain and regret, in how we carry our burdens and how we learn to share them. Give us more stories with lesbian witches and gay cyborgs, queer villains and queer survivors. Let us see ourselves in every facet of what it means to be a person, because we want to be people. We are people.

“Representation politics is complicated, and often irrelevant to whether a given work of art is actually any good. Still, it matters on a level that is difficult to articulate.”

Very difficult, and you nailed it! Thank you for doing so, better than I’ve ever been able to.