[Editor’s note: this post carries a content warning for medical trauma and graphic descriptions of gore]

One of my favorite overused truisms, because of the undeniable utility of it, is that the only difference between medicine and poison is the dose. I’d like to extend upon that platitude and say that the only difference between medicine and body horror is the context. And even that’s a stretch.

There’s a reason why abandoned hospitals and mental institutions discomfit us so much. There’s a reason why many people cannot stomach the sterility of the examining room or the cold touch of a stethoscope, and it has little to do with the mundane unpleasantness of being prodded or poked. The mild sting of a vaccination cannot account for the terror the image of a needle induces. The inconvenience of a pap smear cannot explain the immortal trope of the deranged surgeon; it can’t account for Caligari or Frankenstein, or Science Going Too Far, or the fact that the most annoying killer in the survival-horror game Dead by Daylight—by far—is a doctor.

Medicine has an unshakable connection to horror. Its very premise, after all, is to externally impose traumas that in any other context should be unthinkable—traumas exacerbated by the power differential they represent. The well-known colonialist and abusive history of western medicine (which, to be fair, requires much, much more than a blog post to delve into) provides the basis for many common horror tropes, from involuntary commitment to experimental surgeries. We find easily available precedents in the likes of J. Marion Sims, in the institutions conducting the Tuskegee syphilis study, in the Nuremburg trials. The profession, second only to sex work in its antiquity, has an almost impossibly sordid past of human rights violations—and should we continue to succumb to the absurd imposition of a profit motive on human health, an equally sordid future.

The institution of medicine is a weird, intriguing sort of gothic manor: ancient, prohibitively aristocratic, deceptively fragile and haunted by an evil past. Some of its ghosts are genuinely terrifying, and many remain un-exorcised, leading to devastating inequalities and blatant misuses of power. Others seem to be poltergeists mostly of grave inconvenience (ask a surgery resident why they round on patients at 5:30 in the morning and they’ll likely attribute it to the cocaine-fueled schedule of one Dr. William Stewart Halsted, who pioneered the American residency system over a century ago). But all the ghosts, gone or still lingering, are inspiring in their horror.

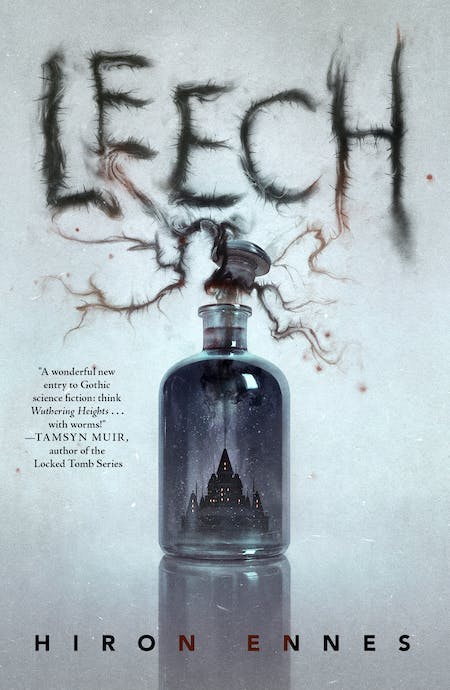

There are, of course, the fan favorites of leeching and trepanning and the fast-paced, murderous surgeries of Dr. Liston. There is the terrifying inhumanity of the butchers of Auschwitz and Unit 731, the covert experiments of the C.I.A. and the monsters who were integrated into the American scientific-industrial complex by Operation Paperclip. There are mad doctors and devious nurses and botched surgeries and biological warfare. But even without the weight of so many societal atrocities, I would argue that medicine is horrifying in a weirder, far more intimate way. Even in the most informed, consensual, and entirely non-malfeasant contexts, almost all of it boils down to committing downright bizarre acts of violence on the body.

The first time I saw an urgent cesarian section, I was floored by the brutality of it. As it happened, the placenta was anteriorly placed, so cutting through the uterine wall was a lesson in splatterpunk—and that was the mild part. What really struck me was the ease with which the surgeon exteriorized and manipulated the uterus, the way she casually pulled out an internal organ and replaced it safely (one of the most important things a student learns in medical school is that organs, ideally, stay inside the body). And even after all that, after the blood and panic, after the surgical removal of an invasive, dangerous foreign body that had almost killed this patient, she took it in her arms and immediately, truly, adored it.

Within hours of starting my surgery rotation, I found myself helping my attending resect a necrotic bowel. This was another emergency; a series of scarry adhesions had strangulated the intestines, killing the flesh, and if left unaddressed, the patient. And so at two in the morning we started open surgery, desperately attempting to reattach what remained of the living tissue. We ensured the integrity of the bowel wall by pouring saline into the patient’s gaping abdominal cavity, then inserting a tube into their rectum and pumping air into it like some bizarre, reverse flatulence. Any bubbles that appeared in the saline pool indicated a leak.

Later that month I saw a patient who had burned his foot and did not receive care until he was in full septic shock with necrotizing fasciitis, what is sometimes colloquially known as “flesh-eating disease.” His was a textbook case, with copious thin discharge and marked crepitus—little bubbles of subcutaneous gas that pop like Rice Krispies under one’s finger (hang around in the medical world enough and you’ll come to learn everything, especially everything that shouldn’t be, is described in terms of food). His leg came off with surprising ease. The bone-saw was swift, and his flesh was so soft, so rotten, we were able to amputate the leg, bag it for pathology and wheel him back out of the operating theater in twenty minutes. It was horrifying, medieval, and by far the most exhilarating day on that service.

Surgery is not the only purveyor of benevolent nastiness; in infectious disease I learned that treatment for recurrent C. difficile is fecal transplant—a pill or enema that contains the bacteria extracted from a donor’s stool (on a related note, you can donate your poop, like blood, to a bank). In oncology I learned that a rare cancer called pseudomyxoma peritonei is partially treated by slicing open the abdomen, literally dumping about a gallon of chemotherapy juice inside, and sloshing it around like dirty laundry. In the medical examiner’s office I learned the pointlessness of holding one’s breath when cutting open a water-bloated corpse, and what stories can be told by the life cycles of maggots. I’ve learned all the weird, invasive tricks: how to properly break your sternum to massage your dying heart, how to cut open your trachea and shove a breathing tube into it, how to insert my finger into your rectum and feel for a boggy prostate. I know how to slice off little pieces of you and examine you in microscopically intimate detail. Though I still can’t manage to play as the doctor on Dead by Daylight.

Sometimes I truly believe the only reason people condescend to visit the hospital is that, no matter how painful the procedures, no matter how traumatizing the loss of corporeal agency might be, what is far worse is what the body can, if left alone, do to itself. For example, you may grow something called a teratoma, an infamous little tumor that will nestle in an ovary and, sorely confused, begin to grow teeth, or hair, or brain cells. You may, if you have a uterus, acquire something called a hydatidiform mole, a pregnancy in which a disjointed meeting of sperm and egg grow not into a fetus, but a bizarre collection of cysts. These pregnancies can be metastatic. They can invade the uterine wall, and from there, the rest of the body. Tuberculosis and chickenpox will live inside you decades after your primary illness, walled off from your immune system, quietly waiting for the right time to remerge. The occasional misfolded protein can drive you fatally insane.

True body horror doesn’t take an approaching white coat with a needle in hand. It requires only that you live in a mutable, mortal body, unaware of what parasites you might be carrying, what dysfunctional genes might be waiting to wake, or what odd exposures might send your confused immune system into disarray. You never know when your own cells will turn against you, you never know when some benign organism in your normal microbiome will proliferate and invade you. Forget medicine, forget its history and abuses and the weirdness of its implementation. Just existing as a biological entity is intrinsically spooky.

It’s nearly impossible to view human biology with any degree of normalcy after one learns just a little too much about how it works—and how it doesn’t. I don’t know where that tipping point lies in one’s medical education, but I’d guess sometime between didactics, when you start fearing the rare and absurd things that might kill you, and clinicals, when you start hoping they might. There is an odd transition when you start to realize exactly how vulnerable the internal human ecosystem is, how flawed, clumsy, how haunted by vestiges of billions of years of evolution—and worse yet, how little you truly know about it.

With that ignorance comes a new kind of terror, a painful but addictive sort of awe. For every broken bone there is an incomprehensibly fantastic process of healing; for each fatal mistake in cell division there is a brilliant tumor-suppressing mechanism; for each pathogen there is a tiny, sleepless factory pumping out antibodies. Every trauma, every triumph, every well-won fight against an invader is recorded at a microscopic level. The memory is retained even through cycles of complete cell turnover, perpetuated in a body partly living, partly dead, and always in a state of deconstruction and restoration like some stupidly complex Ship of Theseus. Every thought, feeling, conundrum, song and story is contained a wrinkled cluster of soft pink goo, and that somehow this goo, by means of ion channels and exocytosis and clever use of bony appendages, has come to know this about itself. Somehow a collection of tiny bags of cytoplasm has, through millennia of trial and error and atrocities and kindnesses, learned to poison itself in just the right amounts.

And that’s just intrinsically kind of terrifying, right?