What is historical horror? If you ask some people, it’s a growing sub-genre of horror. If you ask others, you’ll get a blank-eyed stare.

There’s debate: is it even a thing? What makes a book horror? What makes it historical?

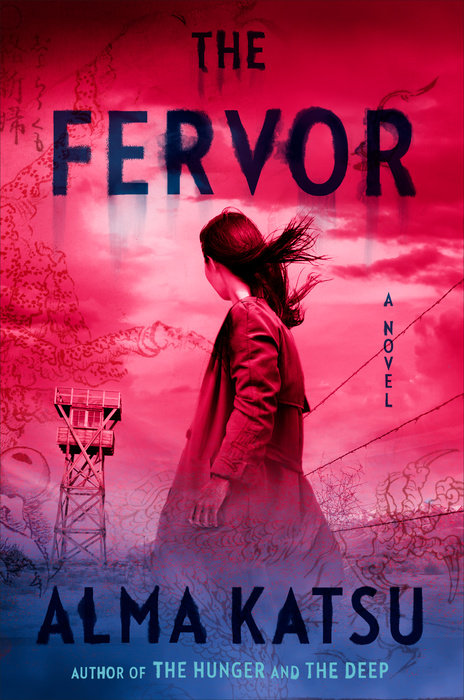

Since I get asked this question a fair amount—my third historical horror novel, The Fervor, comes out shortly—I thought I’d use this opportunity to talk about how to write historical horror. Because there is such debate, however, we need to start with some definitions. Some of these definitions you may agree with, some of which you may not. Opinions vary.

Let’s look at the historical aspect first. I write books that deal with specific historical events: the Donner Party in The Hunger, the sinking of the Titanic in The Deep, and now in The Fervor, the only deaths on the mainland U.S. during WWII and incarceration of people of Japanese descent. This kind of story is most likely to meet the approval of fans of historical fiction, as they tend to like books that are directly and deeply historical. Indeed, most of the feedback I get has to do with readers’ delight at learning there’s more to an event than they’ve been led to believe (secret history? Yes, please!) and how much they enjoy figuring out which pieces are true and which were made up.

Horror novels that are centered around a specific true-life historical event aren’t as common as you might think. Dan Simmons’ The Terror, his well-known account of the lost expedition of Sir John Franklin, is the poster child for this sub-genre. But if you start looking for more books like this, you come up short pretty quickly.

Far more common is the novel that’s set in a previous era but isn’t tied to a singular true event. Many novels fall into this category, where history is an anchor that the author may touch upon throughout the telling but otherwise projects no constraints on the tale. One or two real people may appear in the story, but their actions are not factual. Another way to think of it is that history is providing the setting, but not the plot. You could argue that The Fervor falls in this category: it starts with a specific event (the explosion of a Japanese fu-go, or fire balloon, near Bly, Oregon, which killed one adult and five children) but after that, the events are largely imagined.

What other criteria define the historical novel? In general, the action should take place at least 25 years in the past to be considered “historical”. It’s also supposed to be set in a real place or else it could be considered fantasy. (You may be asking yourself if it wouldn’t be considered fantasy anyway since it has a horror element in it, and you’d be right: horror is generally considered a subset of the fantasy genre. So many definitions! The good news is that no one is out there seeing which boxes you’ve checked. In real life, few people care about such distinctions. They just want to read a good story.)

What’s the difference between historical horror and alternate history? Let’s say you decide to introduce a horde of Sasquatch into the Battle of Little Big Horn. Aren’t you changing history? Yes, you are, and while there are plenty of people who consider all historical horror to be alternate history, I would argue that it has more to do with whether the outcome deviates from history: if Germany won World War II, for example (The Man in the High Castle by Philip K. Dick). But again, this sort of thing is a quibble. You need to think about the expectations of readers of this sub-genre and whether your story is going to meet them or cause them to want to throw your book out the window.

Now for the truly difficult definition: what is horror? The last couple years, it’s become a big tent. If you ask some readers, they’ll say it must include a supernatural element (or, at the very least, that something unexplainable happens). If you ask others, they’ll say it’s filled with blood and gore, like a slasher film. The Horror Writers Association’s definition is straightforward: it’s any story that produces a feeling of terror or horror in the reader. Honestly, whether a story is considered horror or not is up to the individual reader to decide.

To recap: if you’re thinking you might want to try your hand at writing historical horror, here’s a checklist of considerations:

- It’s set at least 25 years in the past.

- It’s tied to an actual place (though you can fudge the names of small cities and towns.)

- Maybe you have a few real people as characters. Or the entire cast. It’s up to you.

- The plot may or may not be dependent on a real historical event.

- Something must occur that causes the reader to feel dread, terror, or great unease.

As you can see, the possibilities are almost endless.

A word on whether you want to use actual people as characters: it’s a bit of an ethical dilemma. Many novels have characters based on real people doing things they would never have done in real life. How comfortable are you with that? Hint: some readers get truly offended. But what if those real people are long dead? I wrote more about that previously for Crime Reads.

One thought on “A Practitioner’s Guide to Writing Historical Horror ”