I’m what you might call a southern-in-law. I was raised in the suburbs of Chicago, a sprawl of housing developments, strip malls, and big-box stores, but my parents grew up in East Tennessee. Both sides of the family trace their lineage back to Cades Cove, a valley that’s now part of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. It’s a gobsmackingly beautiful place, especially in the spring and fall. I’ve visited the cove many, many times over the years, and hiked its trails, including one to the peak of Gregory Bald, the mountain named after my great x5 grandfather, Russell Gregory.

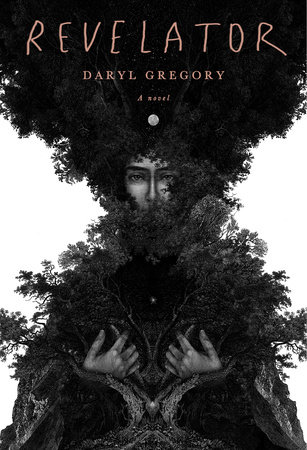

I love the cove, and it’s been a great pleasure to bring my children there. So perhaps it’s a little surprising that both novels I wrote about the area—The Devil’s Alphabet, and my most recent novel, Revelator—are horror stories. Specifically, Southern gothic horror stories.

Southern gothic is having a bit of a moment. Recent novels like Gillian Flynn’s Sharp Objects and Matt Ruff’s Lovecraft Country have reached a lot of readers, and then expanded their audience with TV adaptations. Silvia Moreno-Garcia’s bestselling Mexican Gothic (which I count as extremely-southern-gothic) is in development at Hulu. These stories are full of family secrets and long-buried trauma, often tied to our society’s racist history. Ghosts, both figurative and literal, drift through rotting, vine-covered mansions. Women in these stories are often lied to and manipulated, with everyone around them (especially the family patriarchs) conspiring to keep them silent.

There a couple of reasons why this subgenre, a child of English gothic novels and horror from the American South, still speaks to the way we live today—or more exactly, the way our crowded, busy lives distract us from thinking too deeply about what unsettles and terrifies us. As a writer I’m attracted to these types of stories because it’s a genre engineered to strip characters down so that they can see themselves, and their world, more clearly.

The first step in this distillation process is to isolate the characters. In the real world it can be difficult to escape the hum of traffic. And even when we’re by ourselves we’re not truly alone; our phones are always with us. It’s increasingly rare, and disconcerting, to look down at a screen and see “No Service.”

But in horror stories, isolation is essential. Evil that can be walked away from, or dispelled with a call to the authorities, isn’t ominous at all. Sometimes the isolation is social—the characters don’t think they’ll be believed—or psychological, in that they can’t bring themselves to take the threat seriously. But often social and psychological isolation go hand in hand with being physically cut off from society. Horror writers ship their characters off to a creepy mansion on the hill, or to a remote village, or the quintessential cabin in the woods. The telephone lines have been cut, the ferry can’t make it through the storm, and wifi? We don’t have wifi ‘round here.

Consider the family in Flannery O’Connor’s famous story “A Good Man is Hard to Find.” O’Connor, one of the godmothers of the Southern gothic, sends a white family on a car trip from Georgia to Florida. From the backseat, the grandmother excites the two young children with stories of a nearby plantation that has a secret panel in the wall, and insists the house is just down a road they just passed. The father reluctantly turns around, and heads down a dirt road surrounded by deep woods. Only then does the grandmother realize she’s mistaken; the plantation she remembered is not here, it’s in Tennessee. An accident sends the car into a ravine. The car is immovable, but soon the family is found by three men with guns. They’re criminals, and one is a famous killer, “the Misfit,” a sociopath. The grandmother tries to tell him he’s a “good man,” that he doesn’t have to do what he’s going to do. But there’s no amount of Southern politeness that will save the family.

O’Connor’s story highlights two key elements of Southern horror. First is that nature is beyond human control. It’s indifferent to us, and will swallow the foolish whole. If you’re a city kid like me, take a drive down a country road in Tennessee or Georgia or Mississippi and try not to be overwhelmed by the burgeoning plant life. The lushness of trees and bushes as they push into the road is claustrophobic. The nature of nature is that it’s relentless.

The second element is that it’s only when you leave civilization that you understand the true nature of humanity—and it’s ugly. In the woods, all the trappings of “good society” fall away. O’Connor’s grandmother, early in the story, is sure that in the case of an accident, a passerby would see her fine dress and lovely hat understand that the grandmother is a lady. But when she meets the Misfit, the hat tumbles away, and she dies all the same.

Recently I read James Dickey’s novel Deliverance for the first time, and then re-watched the movie. Four middle-aged “city boys” naively head out on a canoe trip through unmapped waters, in pursuit of a mild adventure, but are completely unprepared for the dangers they face, especially the pair of conscienceless “hillbillies” who stalk and torment them. These rural sociopaths are not portrayed as human beings; they’re forces of nature, as merciless and unreasoning as the rapids the men try to navigate, or the sheer cliffs they’re forced to climb to escape. (Dickey’s not the first writer to reach for a stereotype to try to make his point.) What the survivors gain from this struggle is self-knowledge; they discover whether they’re cowards or heroes. The main character, a reluctant nebbish who at the start of the trip can’t bring himself to shoot a deer, finds the killer within himself and experiences something like transcendence.

In some Southern gothics, the “other” that’s met in the wilderness is supernatural. In Ruff’s Lovecraft Country, set in the Jim Crow era, a Black army veteran named Attticus Turner and his extended family go up against a Klan-style organization of white sorcerers. But unlike O’Connor’s family, who chat about plantations and cheerfully point out poor Black children along the route of their trip, oblivious to the racial divisions in America, Turner’s family is all too aware of the truth of our country, and our history. The supernatural horrors they encounter are nothing compared to the American horrors they’re already living through. They’ll persevere.

Sometimes, however, the truth destroys. That’s what happens in one of my favorite recent Southern gothics, John Hornor Jacobs’ “My Heart Struck Sorrow,” one of two novellas in his collection A Lush and Seething Hell. The story follows Cromwell, a white music archivist at the Library of Congress, as he travels the deep South gathering field recordings of blues songs, especially the cryptic variations of the song “Stagger Lee.” Jacob’s writing is beautiful, and you can practically feel the humidity on your skin. The story, like many Southern gothics, wrestles with race, and poverty, and inherited sin. And Cromwell, like so many characters in all those stories, finds himself drawn into a kind of anti-Eden. The woods and swamps are not a paradise; they’re a proving ground. Cromwell’s encounter with an inhuman creature in the deep woods leaves him not transcendent, but broken.

This is what horror stories, and Southern gothics in particular, do for us: they take us to the places where humans learn the difference between good and evil—and learn whether they are good or evil. Every book is a bite of the apple. Fortunately, in the real world, most of us never have to face such an extreme test. We never have to see the naked truth about ourselves. But still, we’re curious, aren’t we? We want to imagine how, or whether, we’d hold up.

apple

apple

apple

Order Revelator now:

Apple | Bookshop | Amazon | Barnes & Noble | IndieBound

And read Nicole Hill’s review here.

One thought on “Alone in the Garden of Good and Evil: Daryl Gregory on the Southern Gothic”