Every reader has that favorite sentence, the one you turn over and over in your mind, relishing it like a perfect bite of cake or piece of sushi. A sentence that embeds itself so thoroughly in your psyche that it’s difficult to remember how you ever read a story before the one that contained it. The sentence that changes you. Here is mine:

“This being, rooted in change and time, is about to collide with the timeless Gothic eternity of the vampires, for whom all is as it always has been and will be, whose cards always fall in the same pattern.”

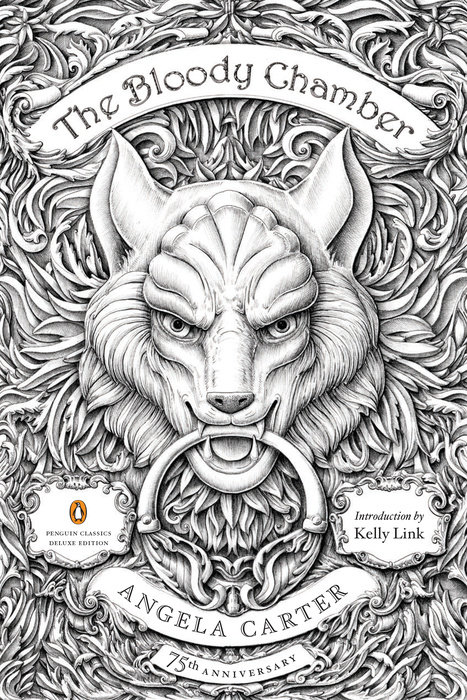

When I first read that sentence a couple of years ago, in Angela Carter’s vampire story “The Lady of the House of Love,” collected in her book The Bloody Chamber, I had to stop for a moment and take a breath. I was riding the train home from work, on my way to pick my son up from kindergarten. It was winter and the afternoon was already dark, the light of day no more than a thin ribbon of orange on the jagged horizon. I read and re-read it until I had it memorized. It’s been in my head ever since.

As with any great story, it’s difficult to isolate this single sentence and explain its brilliance, independent of what comes before and after. Carter was a genius, and “The Lady of the House of Love” in particular is dense; the story itself is a great Gothic castle, every spire, bit of stone lace, and gargoyle in the exact right place. It takes a bold writer to assign an adjective to a concept like eternity; Carter, fearless, assigns two. I’m afraid to take that sentence out of context for you. If I do, the whole thing might come crashing down, as the “timeless Gothic eternity of the vampires” does at the end of the story.

Still, let me try, because the whole thing is in that sentence, and by the whole thing I mean not just this story and its characters and themes, but the entire genre of Vampire fiction, and the birth of the modern world. Let’s examine the elements: change and time, collision, an eternity that is not just forever, but without time, stagnant and still, and Gothic on top of that, with all that word can mean: barbaric, dark, frightening, ornate, bloody, full of secrets and ruins and sex. It’s the violent crash of past and present, creating and foretelling an awful, shattered future.

The story is set in 1914, on the eve of the First World War. In a rotting château somewhere in the Carpathian Mountains of Romania, a “beautiful somnambulist helplessly perpetuates her ancestral crimes.” She wakes at dusk, puts on her mother’s blood-stained wedding dress, lays out the same tarot cards in the same order, and then feeds—usually on rabbits, but sometimes on men.

Carter’s Countess Nosferatu is no Dracula or Carmilla, though, despite sharing their aristocratic rank. Like one of Anne Rice’s more tormented characters in The Vampire Chronicles (which inspired Carter’s story), the Countess does not wish to be a vampire, but has no choice. It’s in her blood. Her vampiric ancestors “sometimes come and peer out the windows of her eyes,” and the story often compares her to an automaton. Her nightly routine never deviates, not even the cards she pulls from the shuffled deck. The Countess is less a monster slaking her lust and thirst on the innocent and unwary, and more a girl fulfilling an unwanted duty, heiress and caretaker of a hideous honor.

In other words, the Countess is not just a vampire, she is The Vampire. It’s the role she plays, not just in the story, but for the story. She’s Carmilla, Dracula, Claudia and Lestat, all rolled into one. Had Carter lived to read Twilight, Edward might have ended up looking out the windows of her eyes, as well (the Countess, we are told, shines with “her own blighted, submarine radiance,” but perhaps she would have sparkled. Anyway, she wishes she could make love to her victims rather than eat them, a sentiment a Cullen could well understand).

Into this endless night comes a young British soldier, “blond, blue-eyed, heavy-muscled,” on furlough from his regiment, and on bicycle. He’s touring the countryside on this modern contraption, “pure reason applied to motion,” as Carter puts it. The soldier is entirely innocent and unknowing, a virgin even, with “power in potentia.” You know this guy, you’ve met him. You’d like to hate him for his good nature, his indefatigable optimism even in the face of the world’s horrors, but you can’t. Tom Holland could play this character in his sleep. These days, on the Internet, we call them golden retrievers, but I like Carter’s alignment with the bicycle. He’s a human bicycle. He’s entirely wholesome.

The soldier stops to rest in the abandoned village beneath the Countess’s castle and, like many a doomed young man before him, is ushered to the vampire’s lair by her mute governess. He’s fed a simple country meal, and then led into the Countess’s suite, where she chatters and serves him coffee, the tired ritual she performs before she feeds. The soldier is both attracted and repelled by the Countess, whom Carter calls “both death and the maiden.” Mostly he pities her.

The soldier is no fool. He recognizes he’s walked into the setting of a ghost story, and is repulsed by the rot and decay of the castle, and the leering portraits of the Countess’s hideous ancestors. But he doesn’t want to be rude to his host, and anyway, he is sustained by a “fundamental disbelief in what he sees before him.” He thinks that there are “some things which, even if they are true, one should not believe.” One might even call this attitude privilege, white and male and Western, a belief that nothing bad will happen to you that is so strong, and so underscored by society, that it can alter reality. Go to any guidebooked village in the Carpathians right now, or any picturesque village or town anywhere in the world, and you’ll find young men (and others, to be fair) from the U.K., the U.S., Canada, Australia, and elsewhere, just like our soldier, often on bicycles even, though often not virgins: young men on adventures into countries where they know not a soul and not a word, sure of their fun and survival, because how else could it go? I know–I’ve been one of them. I don’t have any scars, which proves it.

The Countess invites the soldier to her bedroom. He’s a virgin, but not a prude; he follows. But his sunny presence, his pity and his privilege, have disrupted the Countess’s well-worn routine. She’s flustered. She drops her glasses and cuts her finger on the broken glass, drawing blood. The soldier childishly kisses the wound to make it better, and so drinks her blood. This reversal of the vampiric ritual is too much for the Countess, too much for The Vampire, and so she dies. The soldier finds his bike and returns to his regiment, his only souvenir of the encounter one of the monstrous roses from the vampire’s garden that she gave to him, “plucked from between my thighs.” The next day his regiment departs for the Western Front in France, where, unlike in the vampire’s castle, “he will learn to shudder.”

As in the other stories in The Bloody Chamber, like her retellings of “Blue Beard,” “Beauty and the Beast,” and “Little Red Riding Hood,” Carter dispenses with sexual subtext. It’s all right there on the surface. It suffuses and surrounds the story like the odorous, fanged roses of the Countess’s garden. That’s because the actual subtext of the story is far more lurid and horrifying than the usual sexual anxieties of the vampire tale.

Let’s return to our bicyclist hero. It’s not that he’s the real villain of the story; he’s much too kind for that. It’s what he heralds that is the true monster, a monster far more potent than any vampire. “How can a bicycle ever be an implement of harm?” Carter asks, but of course she knows that, nine years prior to the soldier’s trip to the Countess, two bicycle manufacturers in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina turned that “pure reason applied to motion” into a flying machine; one that’s already been transformed into a terrifying weapon of war, bringing death to mankind in quantities no vampire could ever conceive.

It’s the soldier’s “lack of imagination” that protects him, and lets him unknowingly kill off “the last bud of the poison tree that sprang from the loins of Vlad the Impaler.” The Countess and her grotesque family at least knew they were monsters. But not our soldier. He doesn’t know what he does. Like so many heroes of this modern age who created wonders that transformed into terrors (the internal combustion engine, the splitting of the atom, the internet), the soldier disrupts, sure his own innate goodness is reflected in both his actions and the world around him, leaving the old ways in ruins. That the old ways are horrible isn’t the point—what comes after is even worse. And it will destroy him, too, in the end: the text heavily implies he will die in the trenches. But that’s the nature of this new beast. The horrors of the old world, like the Vampire, were self-sustaining: an endless line down the generations, one after another. The horrors of the modern age, on the other hand, are mechanical ouroboroi, self-replicating and self-consuming.

So the vampire story ends—not only with the death of a vampire, but The Vampire, and all vampires with her. Their timeless Gothic eternity couldn’t survive its collision with a being rooted in change and time. They’re relics of a bygone age; there’s no place for them in the catalogue of horrors of the 20th century. The age of industrialized, scientific warfare had begun. Nosferatu never stood a chance.

oh wow! awesome article. totally got me.