sample heading

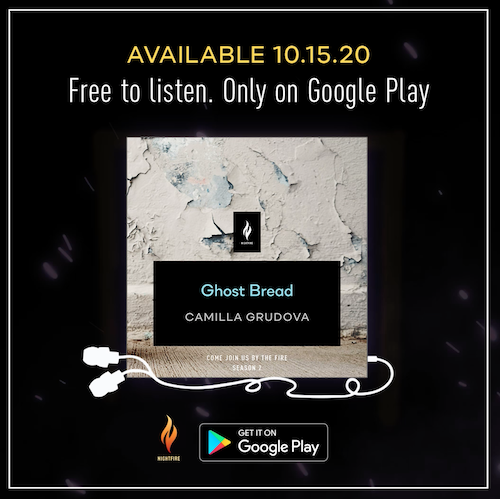

To celebrate the release of the second season of Come Join Us By The Fire, our audio horror anthology, we’ve asked authors with stories included in this year’s anthology to join us and write about horror. Below, Camilla Grudova, whose story “Ghost Bread” you can listen to here, writes about the limited paths for women in midcentury movies.

I see basically every horror film that’s released in cinemas––not because I am a huge fan, but because my day job is a cinema usher and one of my tasks is to check the screens when films are playing, to make sure they’re formatted correctly and that no one is secretly filming or masturbating. I see the films in fragmented, short segments, and I am usually not inclined to sit through the whole feature, because cleaning up the theaters in a dark and musty 106 year-old carnivalesque cinema while the horror film soundtrack plays over the credits is spooky enough. The fragments I do see follow me down to the boiler room as I get another mop head, or through the crumbling cellar trap door as I retrieve another body-sized bag of popcorn. When I cave in and see one, it haunts me for weeks after.

While regular filmgoers can forget the film, I will have to hear the sounds and see the same frightening scenes over and over again, often late at night, after I pass by many Edwardian era mirrors in the dark, one of which has the shadow of a hand on it (the remnant of a Halloween decal from decades ago). The powerful US by Jordon Peele haunted me for months afterward, the old windowless cinema halls I had to walk through late at night when I took the garbage out resemble the underground complex in the film, and I had to avoid catching my own gaze in all those mirrors. I was too chicken to see Midsommar in full after catching peeks of people being flayed and burned alive.

I prefer one-off screenings of old horror films that won’t literally come back to haunt me: The Shining, Don’t Look Now, Rosemary’s Baby. I like the colors of older films, especially when shown on 35mm.

I also like watching old black and white horror films at home, my laptop the size of a cinema screen for dolls, old films too camp to genuinely frighten me, but which still fill me with unease––nausea, even––because of what they say about the human condition. What these older films still say about women’s place in society influence my writing.

Two of my favorite horror/noir films that have lately influenced my writing are Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962) and Sunset Boulevard (1950). Both are set in Hollywood, with plots centered on washed-up female actors from bygone eras. In Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?, a former child vaudeville star and her sister, a starlet of Hollywood’s golden era, live together in a strained relationship in the 1960s. In Sunset Boulevard, a former silent film actress now lives half-forgotten in her mansion, her former director acting as her butler. What the films reveal is that ambition, sexual desire, and pride are all seen as normal in men, but monstrous and grotesque in women, especially older women.

Both have uncanny and unforgettable scenes. In Sunset Boulevard, a dead pet chimp is laid out while its owner, the silent film actress Norma Desmond, awaits a satin-lined child’s coffin. In Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?, the elderly Jane gifts a life-sized doll of herself as a child to her would-be pianist and lover, a drunken mama’s boy who has exaggerated his skills. It’s unsettling that she chooses a vision of herself as a child in her attempt to seduce him, and it almost seems as if she is inviting him to treat the doll like a sex doll, as she looks on, an older woman dressed as her child self, caked-on makeup and Shirley Temple ringlets. Old musty mansions and rats served on silver dishes represent the unhinged and slovenly domesticity of women who care more about their careers.

Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? and Sunset Boulevard draw on older female characters who, like the monster in Frankenstein, are adults uncanny in their childishness, as the source of their horror. Bride of Frankenstein in particular haunts me. The bride, made by Dr. Frankenstein as a mate for his original monster, screams: it’s her first sound upon realizing the reason for her creation. She is screaming at being brought into existence, and at being made specifically for marriage.

It’s no coincidence that the film begins with the same actress, Elsa Lanchester, playing Mary Shelley, telling the story as Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley sit, enraptured. To be born solely to be a wife (and also a mother to the toddler-like monster) is horrible, the source of her scream. By the end, she’s dead, blown up in the building she was created in for rejecting marriage, while Dr. Frankenstein and his fiancee escape and get married themselves.

Mary Shelley’s character seems to get the best of it, her narrative framing an argument that one can have both marriage and career, both love and respect (but anyone with access to Google knows how that ends for Mary).

The Red Shoes (1948) by Powell and Pressburger is another film I would consider horror in the same uncanny mode, and an influence on me. A ballet company is staging a ballet based off the dark fairy tale of Hans Christian Andersen, in which a girl puts on a pair of magic red shoes which make her dance herself to death. The lives of the performers hew closely to the story of the ballet they are performing, and the protagonist, a ballerina torn between her husband and her career, dances herself off a balcony and into the path of an oncoming train, unable to stop, revealing Mary Shelley’s happiness in Bride of Frankenstein as an illusion. With her death, the ballerina avoids both fates: the monstrous continued existence of a career woman past her prime, and the bride’s scream of existential terror.

Camilla Grudova lives in Toronto. She holds a degree in art history and German from McGill University, Montreal. Her fiction has appeared in the White Review and Granta. Her short story collection The Doll’s Alphabet is available now.

Listen to Camilla’s story “Ghost Bread” on Google Play here, and listen the the entirety of the second season of Come Join Us By The Fire here.