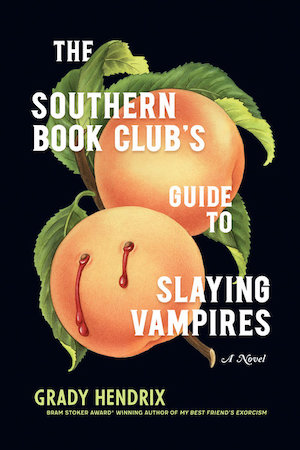

The scene from Grady Hendrix’s latest novel, The Southern Book Club’s Guide to Slaying Vampires, that has seared itself into my brain has little to do with the blood-sucker mentioned in the title.

Apple | Bookshop.org | Amazon | Barnes & Noble | IndieBound

Instead, it’s a meeting of five women and five men, a standoff of wives vs. husbands. The women have been ambushed and now face an interrogation masquerading as an intervention. Their husbands want to know why they’ve become obsessed with a mysterious, charismatic stranger who’s moved in down the block. Why are they harassing him? Accusing him of all sorts of crimes? I mean, murder? My goodness, ladies. All those true-crime novels have rotted your brains, already fragile given the string of bad luck our little community has had lately.

Whatever evidence the women have collected that something’s wrong with their neighbor, James Harris, isn’t enough. It will never be enough. The men have decided. These men like James. They may love their wives, but they like this guy. Patterns can be explained away as coincidences — evidence dismissed as hysteria — because they like this guy. I mean, they wouldn’t like a guy who murdered his aunt. Really, honey, you need to understand that. Don’t you trust them?

The scene ends with Patricia, the central figure of this story and the titular book club, forced to grit out an apology to James Harris. In her own living room. At the demand of her distant, negligent, “I’m doing this for you” husband.

It’s excruciating to read. Particularly as a woman. Particularly as a woman at this time. But it’s also an exhilarating example of what Hendrix has been doing with his unique string of horror novels: exploiting the terrible, awful, no-good things that plague us each and every day.

The Macabre

The Macabre

The Macabre & the Mundane

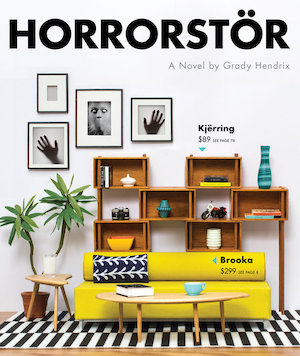

Hendrix gained mainstream attention with Horrorstör, which plumbed the uncharted depths of a simple premise: “What if I wrote a haunted house story but in an IKEA?” It’s a clean, crisp, and beautifully minimal setup — much like the Brooka sofas and Kjërring bookshelves that dot the Orsk showroom.

Apple | Bookshop.org | Amazon | Barnes & Noble | IndieBound

In a Scooby Doo-esque setup, a ragtag group of Orsk employees are tasked with uncovering who — or what — is destroying furniture and wreaking havoc among the pristine displays overnight. As their investigation progresses, it becomes quite clear, quite quickly that there is a literal ghost involved, though the malevolent spirit has to bang the group over the head with a Frånjk or two to force that realization.

It can be hard to process the reality of spiritual possession when you’re dealing with the unrelenting horrors of everyday life. These people work in retail. They know what it’s like to watch a soul pass from a body; they’re less accustomed to seeing one enter a corporeal form. Hendrix captures this perfectly with Amy, an Orsk clerk whose life is seeded with twin worries: 1) paying the bills each month and 2) being stuck paying the bills at Orsk’s Cleveland location for the rest of her life.

Amy’s disenchantment is as real and as insidious as the later-revealed ghost of Warden Worth, if far less malicious. She’s a woman adrift in her own life and now she’s got this to deal with too.

There’s a straight line from Amy in Horrorstör to Patricia Campbell in The Southern Book Club’s Guide to Slaying Vampires. A straight, boring, unremarkable line that nobody pays attention to until an outside force curves it.

Women in Movement

It feels preposterous — a great lowering of the bar — to applaud male authors for well-written female characters. I’m reminded of the infamous George R.R. Martin quote about writing women: “You know, I’ve always considered women to be people.”

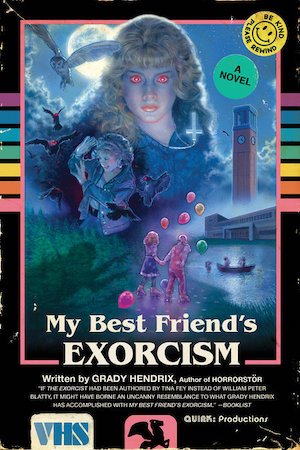

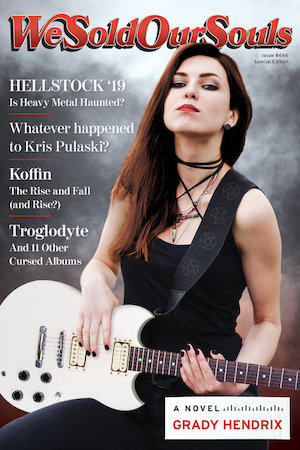

But I am here to applaud Grady Hendrix for writing well-rounded, realistic, perfectly ordinary female characters. Because those characters, in male hands, are still so rare. Amy, Patricia, Kris from We Sold Our Souls, Gretchen and Abby from My Best Friend’s Exorcism — they’re all three-dimensional girls and women with various life paths and a normal array of thoughts, desires, and regrets.

Apple | Bookshop.org | Amazon | Barnes & Noble | IndieBound

What they’re not are The Ass-Kicker, The Brainy Princess, The Best Friend Who Is Actually a Girl, or any of the other standard tropes for women in fiction.

Consider My Best Friend’s Exorcism. Gretchen and Abby are popular, but they don’t resemble the mean-spirited, privileged perception of popular girls. They’re just teenage girls — one with money, one without — who do well in school, have close friendships, and walk a little on the wild side. The toxicity of high school mean girls only comes into play when Gretchen is literally, satanically possessed. This is the story of a demon trying to tear asunder female friendship.

That’s not too far from the scene in The Southern Book Club’s Guide to Slaying Vampires that still haunts me. When the men patronizingly attempt to explain away all of their wives’ misgivings about James Harris, the whole endless production is only partially about the charming vampire they call a friend. These men are there to protect James’ reputation, of course — to smooth things over with their new buddy. But they’re also there to sever the tight-knit bond of their wives, wives who once knew their place as maids and caregivers and domestic darlings (who, in well-to-do Charleston, may also have maids and caregivers and domestic darlings of their own). This little book club, as the husbands see it, not only has slandered the name of a good man but poisoned the minds of their previously compliant wives.

They’re wrong, of course. These kinds of men always are.

The Tragedy of the Convenience

Apple | Bookshop.org | Amazon | Barnes & Noble | IndieBound

Hendrix is a former film critic and pop culture journalist. That experience explains much about his narrative choices and the settings for his novels. (We Sold Our Souls, for example,has as its premise that a rock star sold his former bandmates’ souls to fuel his own success.) He’s also well-versed in using the trappings of pop culture to skewer society at large.

A sparkling, sterile big-box store white-washes the ruins of a heinous panopticon. Musicians suffer a lifetime of mundane misery so their bandmate can get an easy leg up. A teenage girl is suddenly vindictive and cruel, and there are plenty who chalk up the personality change to hormones and high school rather than something more sinister. A series of deaths and disappearances can only be linked in the fevered minds of a group of crime fiction-obsessed housewives.

Hendrix’s oeuvre explores the little lies we tell ourselves, the minute justifications we make to excuse the unexplainable or inexcusable. And when we tally all those little lies — when we finally examine the small sins we’ve let slide? We learn we sold our souls a long time ago, just because it was convenient.

Vampires are scary. Ghosts are frightening. Demons can be deadly. But the real horror Hendrix shows us again and again is what we do entirely on our own. We’re consumed each day with smaller, pettier wrongs. It’s hard even to notice the wolf at the door — especially when we’ve invited it in.

Especially when our wives tell us what we’ve done. Especially when the wolf seems like such a good guy.

I cannot wait to dive into The Southern Book Club’s Guide to Slaying Vampires! I have a copy headed my way! 😀