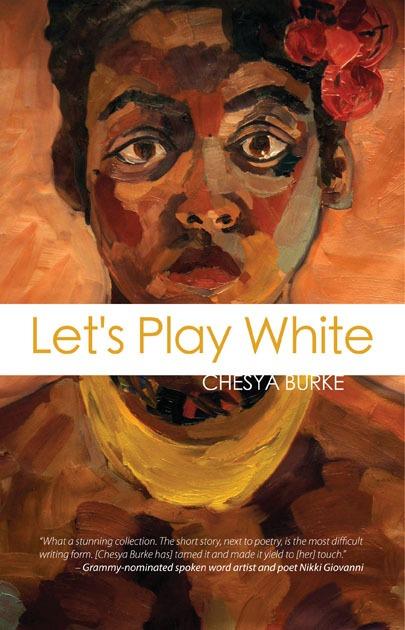

On Being the Other in an Outsider Genre: Interviewing Chesya Burke

We spoke to Dr. Chesya Burke, an Assistant Professor of English and U.S. Literatures and a horror writer in her own right, about Black horror, the intersections of race, gender, and genre, her biggest influences, and writing routines in the time of Covid.

Tyhitia Green: You’ve been writing speculative fiction (and all of its subgenres for years), and your body of work addresses issues of race, gender, socioeconomic status, etc. What made you want to address these important issues in your work?

Chesya Burke: Honestly, I can’t imagine not incorporating these things in my writing. I’ve been “doing” horror long enough (since the mid-2000s or so) that I remember when these issues were rarely, if ever topics within the genre. I can still remember going to conferences and being one of three Black writers. I have been called Aunt Jemima in front of a group full of white men, simply because I was the only Black face in the room. Horror claims to be a “ghetto” genre–and in many ways, it is–so it should be the space for those who are most oppressed, but the truth is race, gender and “the other” issues are considered taboo even in horror. But despite being “the other” in an outsider genre, horror (and sci fi and fantasy) has been the perfect avenue to explore the rage and hurt and anger and pain in which many Black people exist in this world. Black people have a shared history of horror and writing horror is so often about writing our lives within anti-Black societies.

I have written a bit about the way that horror has avoided race, in my essay Horror Is… Not What You Think or Probably Wish it Is for Nightmare Magazine.

TG: What writers have influenced you and your work? And how have they influenced you?

CB: It’s no secret that my favorite writer is Octavia Butler. Sometimes I give a nod to her in my work or play on her themes (my zombie story CUE: Change is a good example). Other writers that have inspired me are Toni Morrison, Zora Neale Hurston (I wrote about her in my dissertation) Richard Wright, W. E. B. Bois, and Tananarive Due. As an academic, I also read a lot of critical work, such as texts from James Baldwin, Nikki Giovanni, Audre Lorde and pretty much everything I can get my hands on.

TG: Black horror in cinema was first recognized when Duane Jones starred in George A. Romero’s 1968 film, Night of the Living Dead. But it wasn’t until after Jordan Peele’s 2017 hit Get Out that Black horror films seemed to be taken a bit more seriously. Why do think that is? As for Black horror authors, do you feel they have that same level of exposure or are they ignored within the genre?

CB: Black people have always loved horror, and it has been an escape for us. The idea that Black people don’t watch horror is akin to the idea that we don’t read books. The book industry learned how wrong they were several years ago when Black people began self-publishing and making a lot of money, and now the movie industry has learned the same lesson. This, of course, is a lesson that the film industry has long ignored, as Black people have saved this industry in the past (in the ’70s with Blaxploitation films, for example). But if history tells us anything, they likely won’t learn this time either.

Get Out works because it is a modern version of a very old story. The good white people that we all know and interact with every day actually aren’t very good at all. In fact, they are more harmful than others. It’s being taken seriously because it’s so blunt. It doesn’t let you look away and it doesn’t let you off the hook. The “bad people” are white people and white people have a lot of work to do around the fact that they are–and continue to be–the horror in Black life.

Interestingly, I have been asked to edit a special issue of an academic journal on Jordan’s Peele’s work. I’m really looking forward to reading how scholars conceptualize him. It’s an exciting time to be a Black horror writer and scholar!

TG: Do you have any interesting rituals you utilize when you write? Listen to music, have the television on/off, snacks, etc.?

CB: No. I really wish I could say that I have some fascinating routine to help me write, but I really just sit my butt in the seat and start writing from the first page to the last. I will say that Covid-19 has changed it a bit, though. I’ve always had writing sessions with fellow writers and quarantine has just increased that. My friends and I with book projects will hop on Zoom or Google Meet and write/talk/write/talk. It breaks up the monotony and forces us to get the work done. Now, during Covid-19, I have about 4 different writing sessions with different friends (depending on if it’s academic work or fiction) per week. It’s good to bounce ideas off each other, but also to keep in touch when so many of us haven’t seen each other in nearly a year now.

TG: What are you working on and what upcoming projects do you have coming out? Where can readers find you via the web?

CB: My website is thechesyaburke.com. I recently started a Patreon, which is looking desperately lonely, so feel free to follow me there.

I have a story in Hex Life: Wicked New Tales of Witchery, just turned in my story for Dark Stars, a new anthology of novelettes from Nightfire, finished a middle grade book, and am working on a sci-fi novel based in the same world as my short story “Say, She Toy” (trigger warning for violence). And for those interested in the academic side, I’m finishing up writing my monograph, Hero Me Not, about the character Storm from X-Men for Rutgers University Press.

As for stories to read now, “Please, Momma” and “I Make People Do Bad Things” are both up at Nightmare Magazine.