Small Screen Horror

Continuing my examination of overlooked or undervalued “horror” anthology television series, I thought I’d pivot away from HBO’s The Hitchhiker (to return to season two at a later date, fear not) to sample a rarer vintage.

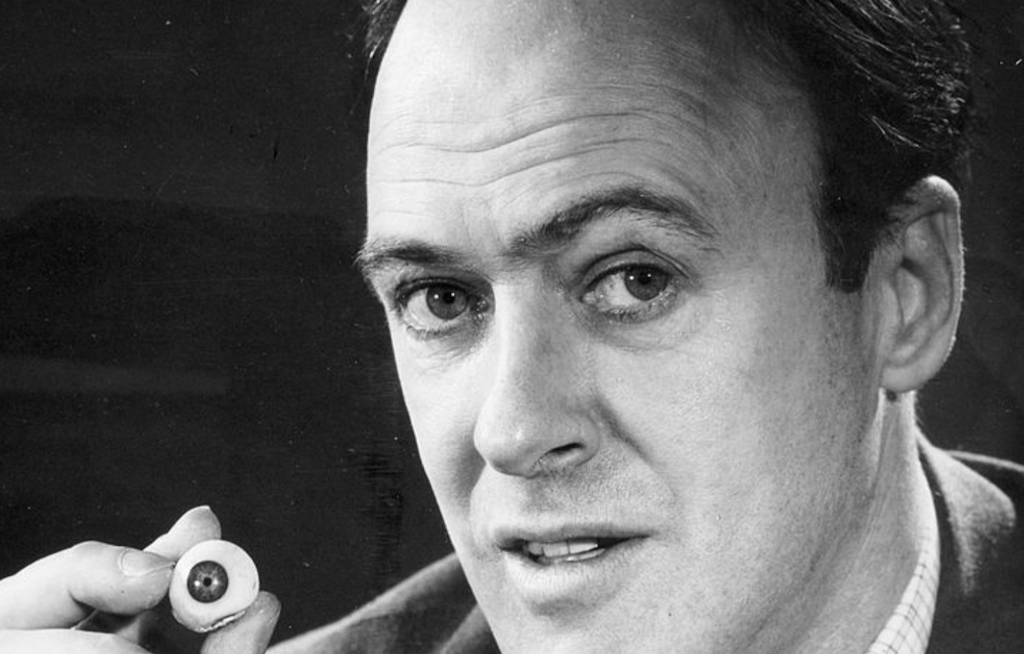

Sixty years ago (following the disastrous debut of Jackie Gleason’s ill-considered quiz show You’re In The Picture – look it up, a real stinker), CBS needed a show to fill a sudden gap in the schedule. Enter television innovator David Susskind, who had wanted to produce an anthology showcase of scary stories. Cue Susskind’s desire to have the show filmed in Manhattan and to have sardonic short-fiction author Roald Dahl (stuck in New York City following a near-fatal street accident involving his infant son) host the program, a la Rod Serling. And so, lights up on ‘Way Out (the initial apostrophe considered important, to indicate the colloquialism and not a direction) which ran for 14 episodes, from March to July of 1961, and then… slipped down the memory hole of entertainment history.

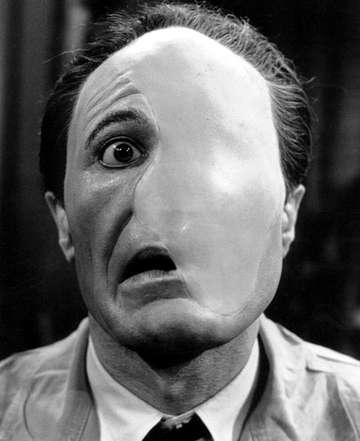

I first encountered ‘Way Out as an entry in the seminal overview/episode guide Fantastic Television (1977) by Gary Gerani & Paul H. Schulman. Many years later, attending an old-time radio convention, I was able to score a videotape containing five episodes of this rarity and, just a few years ago, those and a further five appeared on YouTube. Anyone who remembers the show fondly (or who has seen a still of the extremely striking “blanked face” makeup job by Dick Smith from the ‘lost’ episode “Soft Focus”) has wanted to view the series in its entirety. That dream remains thwarted, but let’s look at what we CAN see…

Roald Dahl had been enjoying bestseller success with his story compilation Kiss, Kiss (1960), as well as various television adaptations of his curdled tales. Susskind desired a show that assiduously avoided the genres of sci-fi (already dominated by The Twilight Zone), the paranormal (One Step Beyond’s provenance), and straight crime/mystery tales (the domain of Alfred Hitchcock Presents). Instead, ‘Way Out was conceived as aiming for black-humored, offbeat, and macabre stories that offered no moral redemptions (its characters generally just suffer their fates for their indiscretions) and few ghosts. The programming chief referred to it, at the time, as an “experimental” show, and so was born one of the earliest examples of the “Conte Cruel” anthology TV show, resonating heavily with the gruesome comeuppance yarns that had previously appeared in EC comics like Tales From The Crypt. Such a formula proved to be a perfect fit for the droll and sardonic Dahl, who once proclaimed “the human race annoys me.” The only demand of the show’s sponsor, L&M Cigarettes, was that there be copious smoking in the stories and by the host.

And so, following a stark opening featuring a weird, blazing “hand of glory” (a replacement for the initial episode’s “fractured eye,” which was seen as negative reference to CBS’ logo), Dahl would calmly but ghoulishly discuss some death custom, or offer various methods for spousal murder, and then off we would go… ‘way out…

Modern viewers should make a concerted effort to understand the show’s context. ‘Way Out was not slick television shot on film in MGM’s backlot (like The Twilight Zone). Instead, you’re watching shot-on-videotape productions in New York City, which feel more liked filmed stage plays (the show was not transmitted live, as sometime erroneously reported). The producer, by the way, was Jacqueline Babbin, one of the first women in that field at the time. The initial episode, “William & Mary” (later filmed as an episode of the British series Roald Dahl’s Tales Of The Unexpected in 1979), was the only Dahl story to be adapted, although his story “Skin” was also purchased and scheduled for production before the series was cancelled.

The show featured a jarring and sometimes abrasive sound mix, utilizing echo, reverb, and avant-garde electronic music by notable composers in that field like Otto Luening, Vladimir Ussachevsky, and Tod Dockstader, as well as incidental music by Robert Cobert (who later went on to fame composing for Dan Curtis productions like Dark Shadows). Famed makeup artist Dick Smith handled the practical effects (most notably on “False Face” and “Soft Focus”–the latter of which inspired a young Rick Baker to pursue a career in the field).

Of the episodes available for viewing, “I Heard You Calling Me” is the most negligible, as a woman planning to flee London with a married man begins to receive threatening phone calls in what is ultimately a nonsensical ghost story. The show’s focus on black humor is featured strongly in a quartet of episodes: “William & Mary” features a dyspeptic genius, diagnosed with a fatal disease, offered a scientific way of cheating death–but his abusive treatment of his wife catches up to him (the episode also features the knowing inclusion of a loaded phrase from technological history with “Watson, come here, I need you.”). In “The Croaker,” a bratty delinquent-in-training (who breaks into people’s houses and steals their pets, only to collect the reward money for their return) runs afoul of his creepy neighbor who seems obsessed with frogs–but who is a danger to who? John McGiver is quite fun to watch as the batrachian Mr. Rana in this silly and sick black comedy. An unhappy husband with a TV-addicted wife, in “Death Wish” contemplates a homicidal offer from Ogilvie & Petard, Morticians (“Let Us Dispose of the Body”) in an episode with a vaguely Alfred Hitchcock Presents feel to it, with some murderous banter and an ending that has a nicely unearthly and nightmarish quality. In “Hush-Hush,” a milquetoast scientist invents a way of pacifying animals with sound, but his use of the device on his demanding wife has unintended and deadly effects. While not a strong episode, this also ends on an effective, well-chosen fade-out.

The series finale, “20/20,” is about an encyclopedia salesman who, thanks to his faulty new glasses, contacts an unearthly couple of taxidermists, The Jellifers (representatives for the Society for the Eradication of People), who offer their services in the murder of his belittling wife. While this is a little too close to “Death Wish” (and even replicates that episode’s twist), The Jellifers are memorable oddballs who are unsettling in the way they justify their “business.”

“The Overnight Case”

“The Overnight Case” may be the ringer in the series, offering a story that vacillates between two Twilight Zone episodes (“Person or Persons Unknown” and “Perchance To Dream”) as a woman repeatedly awakens from a nightmare (centered on a half-packed suitcase) to find herself with a different name and her husband a stranger each time. With its puzzle box construction, this moody dream-within-a-dream-within-a-dream scenario anticipates Christopher Nolan’s Inception (2010) while playing out its own psychodrama, which manages some eerie and tense moments.

“False Face”

But there are three truly outstanding episodes that showcase ‘Way Out at its best. “False Face” involves a hideous, drunken derelict who an aspiring stage actor uses as his makeup model for a role as Quasimodo in The Hunchback Of Notre Dame… but you can’t steal a man’s face that easily. This is a simple and effective story written by Larry Cohen (It’s Alive, God Told Me To, The Stuff) and the closest the show gets to Tales From The Crypt territory, featuring some powerful makeup work by Dick Smith and some inspired acting (I love the way the actor cruelly mimics the derelict’s physical expressions of real pain and despair in order to incorporate them into his role).

“Side Show”

Harold Potter, a dissatisfied husband, escapes his controlling wife and visits the carnival, but a trip to the “Side Show” introduces him to Cassandra, The Electric Woman (a decapitated beauty with only a light bulb for a head). Convinced she is only a trick, but also that she is held captive, he makes a daring plan to rescue Cassandra. This episode has a weird, seedy and macabre atmosphere, encapsulating everything the show was striving for, and features solid dialogue (Wife: “Who was the woman you spoke to? Was she pretty?” Harold (considering): “N-n-not in a conventional way…”) and pointed lines (Cassandra: “EVERYTHING’s done with mirrors, dear”).

“Dissolve to Black”

“Dissolve To Black” is my choice for the show’s best episode. A fledgling actress calls late at a television studio for a fill-in role (as a witness to a murder who is then murdered herself), but when the director asks her to stay late, and all the lights go out, she finds the studio and set occupied by the “Night Crew”–mute, ghoulish, pale-faced sleepwalkers–who seemingly desire to replicate the scenario for real, even as the disembodied voice of the director guides them all through the murderous action. It’s notable that thirty-minute anthology shows can occasionally pivot to an episode like this–not so much a story as a scenario–where a longer format absolutely demands more of a plot. Here, with its canny use of an empty television studio, exposed set backdrops, and resonant dialogue (“You just get killed and we dissolve”), ‘Way Out excels at conjuring the feel of being trapped in a real, illogical nightmare. The closest approximation I can give is a melding of The Twilight Zone episode “The After Hours” and the perennial late-night classic film by Herke Harvey, 1962’s Carnival of Souls.

I would like to acknowledge the excellent book by Martin Grams Jr. that examines the history of the series: ‘Way Out (2019). Grams’ work is truly thorough and exacting–he seems to have had access to many of Susskind’s internal documents and letters, so you can learn who was paid what, alternate actors considered for roles, proposed stories, and quotes from outraged viewer’s letters (this last aspect is truly eye-opening, as we tend to telescope the past and forget that groups like the Legion of Decency would provide members with “talking points” to organize around). The book is truly a labor of love, and you can learn more on the author’s website here.

This is merely an overview to a fascinating piece of lost genre history. Reportedly, the other four episodes are available in some television museums, so we can all hope that some ambitious DVD or streaming company might clear the rights and make them all available again.

This post was written for Nightfire in partnership with Pseudopod.

I would love to see from ‘Way out…episodes 1. soft focus

2. the sisters

3. Button Button

4. The down car

Where can I find or purchase these 4 episodes. Thank you Rochelle

A stated in the article, they only seem to be available for viewing at some television museums