“It made me feel thrillingly horrible.”

These are some of the first words that Rose Nemser gets out upon meeting a cantankerous Shirley Jackson in the new movie Shirley, now streaming on Hulu. They serve as a rather succinct review of “The Lottery,” the deceptive and dark short story that first shot Jackson to prominence. But those words also make for a quick summary of director Josephine Decker’s moody, gothic, and claustrophobic film.

Until recently, Shirley Jackson’s oeuvre of unsettling horror stories largely spoke for her. She was only 48 when she died in 1965, and her reclusive lifestyle has shrouded her in our collective memory. But her stories — including the genre staple The Haunting of Hill House — spoke loud and clear about her remarkable, macabre mind, influencing generations of writers who followed.

Apple | Bookshop.org | Amazon | Barnes & Noble | IndieBound

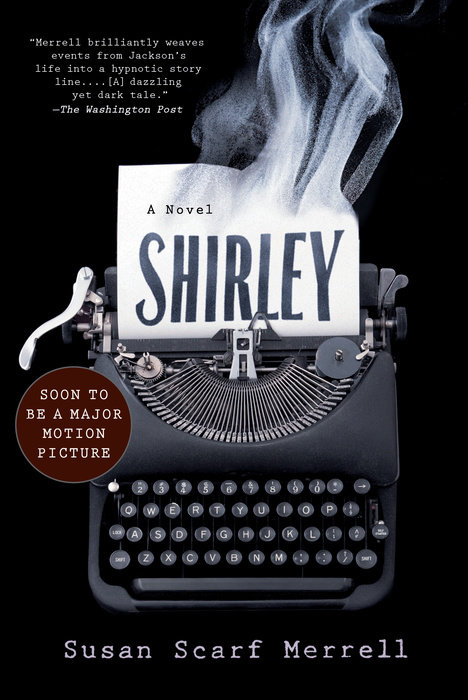

Now here she is. Or, at least, a version of her. The movie Shirley, with Elizabeth Moss as its Jackson, is an adaptation of Susan Scarf Merrell’s 2014 novel of the same name. That novel dispatches a young fictional couple, Fred (Logan Lerman) and pregnant Rose (Odessa Young), to live with Jackson and her professor husband, Stanley Hyman (Michael Stuhlbarg), when Fred starts his academic career under Stanley’s tutelage.

That move-in is where the movie starts, and where things become “thrillingly horrible,” as this version of Shirley Jackson’s life sprinkles in the very elements that made her stories so unnerving.

What Lies Beneath

What Lies Beneath

What Lies Beneath

What’s the gothic version of Cottagecore? Whatever it is, it’s as close as I can come to describing Shirley’s aesthetic. There is Shirley Jackson, rambling around her finely adorned, ivy-covered home, careworn from neglect. There are Shirley and Rose, traipsing through emerald-green woods, stumbling upon pockets of mushrooms. There, too, are scads of brightly dressed coeds on a pastoral Vermont campus, over which hangs the grim disappearance of one of their own.

The film, like the book it’s based on, is a Red Delicious apple hiding a maggot-eaten core. It’s a wonderful homage to Jackson’s best-known works, all of which expose the dirty underbellies of their preening, lustrous subjects — whether they be a grand house or a “respectable” town.

This story picks at those deceptions. There are the two marriages at its center, neither of which are easily characterized or understood by those in them. There is also the town of Bennington, Vermont, which shies away from questions about a long-missing college student. That particular raw point is one this Jackson continually probes, turning the real-life disappearance into her novel Hangsaman. (The timeline of the movie and Merrell’s novel is a bit wacky; Hangsaman was written earlier in Jackson’s career than this condensed version of events suggests.)

The disappearance of that girl — a student at the college where Stanley teaches — haunts Shirley, as does the novel-writing process. Her husband’s alternating role as cheerleader and bully doesn’t help. But when he questions whether Shirley even understands the girl well enough to write her, something sparks.

“There are thousands like her,” she tells him. “Lonely girls who cannot make the world see them. Don’t you tell me I don’t know this girl. Don’t you dare.”

This Art of Misdirection

Jackson never wrote the novel or short story you expected after reading the first line. Her brilliance came in surprising you, shifting you subtly to the narrative she wanted you to read.

In Shirley, no one conveyed this to Fred or Stanley, who spend most of their screen time in a petty academic power struggle, with Fred agitating for more respect and responsibility. (Stanley holds his control of the classroom as tightly as he attempts to control his wife’s creative process.)

Now, I couldn’t care less about Fred’s ordeal. I couldn’t care less about Stanley’s stranglehold on his fiefdom. Their textbook testosterone-fest aims to suck some of the oxygen from Shirley and Rose’s complex relationship, and it seems all the more pathetic for the attempt.

You see, Fred doesn’t understand he’s the B plot. He doesn’t recognize that he’s the side character. This, unlike everything else in his life, isn’t about him. It’s about, as Stanley says elsewhere, “the wifey.” It’s about two women, unseen to all except each other and, even then, only glimpsed.

Stanley has set Rose as Shirley’s minder, the one who will make sure she gets out of bed and eats a meal. So they spend considerable amounts of time together at the house, turning initial enmity to tentative friendship to possibly something else entirely. They are two against the world, or at least against their irritating husbands and the college’s snooty society. They two, diving into Shirley’s novel and, in hazy moments, melding with its story of a lost girl.

The actions of men start and end the movie. But this is a story about lost girls, those who can’t quite find their way to the role they’re supposed to play. Those who can’t find it in themselves to excuse their husbands’ infidelities and failings. Those who can’t find the normal playbook.

“Let’s pray for a boy,” Shirley tells Rose as her pregnant belly grows. “The world is too cruel to girls.”

The Haunting of Hyman House

All of this plays out largely in and around Shirley and Stanley’s home. Shirley’s been cooped up there for months when the movie opens. She leaves only on a handful of occasions, at Rose’s prompting, in its duration. Townspeople speak of her as a specter, much the same way as villagers murmur about the Blackwoods in We Have Always Lived in the Castle, Jackson’s final novel.

In the film, the focus is on her social anxieties, which hang over the house like a miasma. She’s unable to go out, to hold a dinnertime conversation without lashing out, or even to write. In Rose, she finds a bit of a muse — a real-life stand-in for the lonely girl of her planned novel.

Much like her stories, Shirley’s relationship with Rose is out-of-focus, blurred at its edges. The final notes of it, as Rose and Fred move out of the Hyman house, are dream-like and uncertain. There are no final lines between them, no shaken hands or kissed cheeks. Just an abrupt ending to an unlikely partnership, a mirror to the abrupt ending of Jackson’s life and career a precious few years after the final scenes of this fictionalized account.

But Shirley Jackson will have the last laugh, the final word. She does in this movie. She has, even in death, through her writings. Long after we’ve all left the dinner table, she will be there, eating the mashed potatoes straight out of the serving dish and making you wonder just what she’s thinking.

Shirley is now streaming on Hulu.